Original Scientific Paper

UDC: 338.481.1

338.482:316.776.3

DOI: 10.5937/menhottur2500006V

eWOM as a key factor in consumer intent to visit a destination: The moderating role of trust

Julija Vidosavljević1[*], Nađa Đurić1

1 University of Kragujevac, Faculty of Economics, Kragujevac, Serbia

Abstract

Purpose – Considering the intangible nature of tourism services prior to consumption, effective communication and experience exchange with other users are of critical importance. The rise in digital media usage, with the credibility of WOM communication, has led to the increasing role and significance of e-WOM in tourism. The purpose of the paper is to uncover the broader impact of e‑WOM on tourists’ decision‑making by exploring its effects on destination image and tourists’ attitudes. This study aims to examine how e-WOM, through destination image and attitude, influences the intent to visit a destination. The study also explores the moderating role of trust. Methodology – The methodology involves conducting reliability analysis, correlation analysis, and both simple and moderation regression analyses. Findings – The findings show that e-WOM positively influences tourists’ trust and attitudes, and that both trust and attitudes positively affect their intention to visit a destination. Implications – The implications of this research highlight the importance of effectively managing e-WOM, encouraging positive reviews, and addressing negative feedback in order to shape tourists’ attitudes. It highlights the importance of maintaining a strong destination image through targeted promotions and emotional connections. Trust-building through transparency and authentic communication is crucial for attracting visitors.

Keywords: eWOM, trust, destination image

JEL classification: M31, Z30

eWOM kao ključni faktor potrošačke namere za posetom destinaciji: Moderatorska uloga poverenja

Sažetak

Svrha – S obzirom na nematerijalnu prirodu turističkih usluga, efikasna komunikacija i razmena iskustava sa drugim korisnicima je od ključne važnosti. Porast upotrebe digitalnih medija, zajedno sa kredibilitetom WOM komunikacije, doveo je do povećanja uloge i značaja e-WOM-a u turizmu. Svrha rada je ispitati širi obuhvat uticaja e‑WOM komunikacije na odluke turista, istražujući njegove efekte na imidž destinacije i stavove turista. Cilj rada je ispitati na koji način e-WOM, preko imidža destinacije i stava o destinaciji, utiče na nameru za posetu destinacije. Pored toga, u radu je ispitivana moderatorska uloga poverenja. Metodologija – Metodologija obuhvata analizu pouzdanosti, korelacionu analizu, prostu i moderacijsku regresionu analizu. Rezultati – Dobijeni rezultati pokazuju da eWOM pozitivno utiče na poverenje i stavove turista. Poverenje i stavovi turista pozitivno utiču na njihovu nameru za posetu destinacije. Implikacije – Implikacije istraživanja naglašavaju potrebu za efikasnim upravljanjem e-WOM-om, podsticanjem pozitivnih recenzija i rešavanjem negativnih povratnih informacija kako bi se oblikovali stavovi turista. Ističe se važnost održavanja imidža destinacije kroz ciljane promocije i emocionalnu povezanost, kao i građenja poverenja kroz transparentnost i autentičnu komunikaciju.

Klјučne reči: eWOM, poverenje, imidž destinacije

JEL klasifikacija: M31, Z30

1. Introduction

Travel has now become an integral part of people’s lives. As living standards rise, individuals increasingly seek leisure activities and sources of enjoyment, as tourism (Deb et al., 2024). Prior to embarking on trips, individuals commonly seek supplementary information (Yan et al., 2018). Additionally, the tourism sector is distinguished by the exchange of travel experiences across both offline and online channels (Litvin et al., 2008). The importance of interpersonal communication is emphasized, given the intangible nature of tourism and the inability to experience or evaluate services prior to purchase (Grubor et al., 2019; Philips et al., 2013;). Therefore, interpersonal communication (word-of-mouth - WOM) is often highlighted as the most significant source of information when it comes to making travel decisions among users (Litvin et al., 2008; Marić et al., 2024). It is emphasized that in today’s era, the word “friend” is most often associated with Facebook, “community” with networks, and the term “word of mouth” was traditionally linked to personal interpersonal communication outside social media. Nowadays, according to a report by Nielsen (2023), 92% of consumers in America trust recommendations from family and friends more than paid advertisements. Meanwhile, 84% of consumers trust online reviews and comments as much as they trust recommendations from members of their reference groups.

With the onset of internet usage for commercial purposes, the volume and speed of communication among people have increased significantly (Marić et al., 2017). Social networks enable fast, clear, and efficient information transfer to recipients, resulting in more intense communication, which in turn leads to increased trust and loyalty.

The percentage of social media users in Serbia has been above 90% for years. The highest annual growth was recorded in the age group between 55 and 64 years. Most users have accounts on Facebook (89%) and Instagram (75%), while TikTok saw the highest annual growth in 2022, with a quarter of Serbia’s population now having an account on the platform. Research conducted by Social Serbia (2024) shows that 51% of social media users in Serbia use it for information, 39% for searching companies and brands, and about 27% use it for online shopping. With nearly 90% of the population accessing social media via mobile phones, it’s notable that close to 7 billion people now own smartphones. Compared to the world population of 8 billion, about 80% of people have a smartphone, with Serbia being above the global average in terms of mobile device ownership. Mobile device penetration in the Republic of Serbia is 123.9%, indicating an average of 123 mobile devices for every 100 residents (Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2023).

Given the importance of electronic interpersonal communication in the modern environment, this study aims to examine how e-WOM, through destination image and attitude, influences the intent to visit a destination. Additionally, it examines how trust, a crucial factor in electronic communication, plays a role in the relationship between e-WOM and the intent to visit a tourist destination. Conducted in Central Serbia from June to August 2024, the research applies various scientific methods, including reliability analysis, correlation analysis, simple regression analysis, and moderation regression analysis, to derive its findings.

2. Background

2.1. From personal to electronic WOM

Interpersonal, oral, or WOM (word of mouth) communication is cited as a powerful marketing tool. According to Senić and Senić (2008) “the process of word-of-mouth communication involves verbal communication between the sender and the receiver, related to a product, brand, or service” (p. 121). After a period of inactivity, the topic of WOM resurfaced at the end of the 20th century as technology enabled consumers to share content online. By posting comments, ratings, and reviews about companies and their products, consumers created “electronic word of mouth” (Mitić, 2020).

Positive word of mouth is one of the most effective ways for companies to sell products and services. From the consumer’s perspective, it facilitates decision-making in choosing a particular brand (Marinković et al., 2012). Given the number of paid advertisements consumers are exposed to daily, it is not surprising that positive WOM has a much stronger influence on their opinion of products and services (Abubakar & Ilkan, 2016; Sweeney et al., 2008). More importantly, a person spreading positive word of mouth has no financial interest, which gives this form of communication a high level of credibility and makes it more accepted by consumers (Marinković et al., 2012).

Today, as internet usage increases, the way people read, write, gather information, and share experiences is evolving (Kocić & Radaković, 2019). The emergence and expansion of the internet have led to the development of a new paradigm of interpersonal communication – electronic WOM (Aprilia & Kusmuawati, 2021). The concept of electronic interpersonal communication (e-WOM) emerged in the mid-1990s, coinciding with the Internet’s transformation of how users engage with products and services (Chu et al., 2019). Unlike traditional offline interpersonal communication, which involves direct verbal exchanges between individuals in physical contact, electronic (online) interpersonal communication is the transmission of opinions, statements, and attitudes through electronically recorded words. The main advantage of electronically recorded words over verbal communication lies in the ability to spread the word from one location, for example, from home, without making an additional effort or using other resources. Electronically recorded words are more formal and are usually considered more sincere because they are unchangeable (Marić et al., 2017). On the other hand, user opinions can be risky because the company cannot control them. However, in today’s cyber environment, users increasingly trust other users’ comments precisely because they are not affiliated with or paid by the company (Martini, 2022).

Electronic interpersonal communication can be defined as “any positive or negative statement made by potential, current, or former customers about a product or company, which is available to a large number of people and institutions via the Internet” (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004, p. 39), including social networks and mobile communications (Chu et al., 2019). This form of communication occurs entirely in a digital space, including social networks, content-sharing sites, microblogs, forums, and other platforms that facilitate the sharing of opinions, experiences, and attitudes among various products and service users (Kocić & Radaković, 2019).

Although marketers and tourism managers strive to develop and present a favorable image of a destination, other factors also influence tourists’ decision-making. Tourists communicate with each other, and the information from others significantly shapes the decision-making process in this industry. For this reason, eWOM has long been acknowledged as a powerful influence in tourism (Grubor et al., 2019). In the virtual environment, tourists exchange knowledge and information about destinations and overall experiences. All information about services, destinations, institutions, and products is defined as eWOM in tourism and is important to the public as it represents a written form of user experiences (Ran et al., 2021) without commercial interest (Ye et al., 2011). It is particularly effective in searching for information, evaluating, and making subsequent consumer decisions.

Since travel-related products are considered high-engagement and high-risk services for consumers (Mirić & Marinković, 2023), the inability to experience them before purchase makes decision-making challenging. Research indicates that over 74% of travelers rely on online reviews and comments from other travelers when planning a trip (Yoo & Gretzel, 2011) highlighting the growing importance of online reviews as a key information source in tourism (Teng et al., 2014).

2.2. Hypotheses and research model

2.2.1. Attitude toward destination

Attitudes can be defined as relatively permanent and stable favorable or unfavorable evaluations of an object (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) and, as such, represent an important psychological construct, as they influence and predict many behaviors (Jalilvand & Samiei, 2012). According to Ajzen (2001), “the more favorable the attitude toward a given behavior, the stronger the intention to perform that behavior” (p. 28). In the context of this study, attitudes toward a tourist destination refer to “psychological tendencies expressed through the positive or negative evaluation of tourists when engaged in specific behaviors (e.g., visiting the destination)” (Jalilvand & Samiei, 2012, p. 136). Studies have shown that online interpersonal communication has a crucial impact on shaping consumer attitudes and behaviors (Zarrad & Debabi, 2015). Numerous studies confirm the positive impact of both positive (Choirisa et al., 2021; Harahap & Dwita, 2020; Miao, 2015) and negative e-WOM communication on tourists’ attitudes (Lee & Cranage, 2014). Several studies have shown that attitudes are predictors of destination intention. Furthermore, marketing literature (Lee & Cranage, 2014; Miao, 2015; Sparks & Browning, 2011) has shown that attitude has a strong positive effect on the intention to revisit the destination. Accordingly, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

H1: E-WOM positively influences tourists’ attitudes toward a tourist destination.

H2: Attitudes toward a tourist destination positively influence the intention to visit the destination.

2.2.2. Destination image

Chi et al. (2008) state that “destination image is an individual’s perception of a place used as a destination” (p. 626). Destination image encompasses various characteristics and information about the climate, infrastructure, population, culture, as well as assessments of attractiveness, safety, and more (Goyal & Taneja, 2023). In today’s business environment, maintaining a positive image is crucial for success (Filipović et al. 2023). Destination image directly influences how tourists perceive the quality of the tourism product, affecting their evaluation of the experience. The way tourists assess their experience will impact their likelihood of returning and their propensity to recommend the destination to others (Marković et al. 2024), so it can be said that it is an important determinant of tourist intenton to revisit the destination (Alsheikh et al., 2021; Paisri et al., 2022; Seow et al., 2024; Sharipudin et al., 2023).

Today, the commercial sources of information are overlooked in the context of developing awareness of a particular tourist destination, with eWOM standing out as the primary communication source that contributes most to forming destination image awareness (Doosti et al., 2016). Destination image is shaped by various factors, including the safety, culture, and natural environment of the place. Hamouda and Yacoub (2018) propose that the emotional dimension of a destination’s image is crucial for motivating tourist visits, with e‑WOM significantly shaping that emotional connection.

Numerous studies have shown that destination image is one of the primary predictors of a tourist destination’s popularity (Chu et al., 2022), attitudes (Jalilvand & Heidari, 2017), and tourist satisfaction (Chi & Qu, 2008; Girish et al., 2017). Although eWOM is highlighted as a significant driver of a positive destination image, research conducted by Jalilvand and Heidari (2017) shows a stronger impact of WOM on the destination image compared to eWOM. In the research carried out by Jalilvand et al. (2012), positive electronic interpersonal communication is emphasized, because positive experiences with a destination is a significant factor that influences the destination image positively. Tourists’ intentions can be partially predicted based on the destination image, thus influencing the process of selecting a particular destination (Doosti et al., 2016). The effect of a city’s overall destination image on the intention to visit has been studied by numerous researchers (Kim & Lee, 2015; Park & Nunkoo, 2013). Yang et al. (2024) found that eWOM significantly enhances destination image - likely because tourists often turn to the internet as their first resource for researching and selecting a travel destination. Based on the aforementioned, the following hypotheses can be defined:

H3: e-WOM positively influences the destination image.

H4: Destination image positively influences the intention to visit the destination.

2.2.3. The moderating effect of trust

“From a general point of view, trust refers to a willingness to rely on an exchange partner” (Ladhari & Michaud, 2015, p. 38). When consumers trust a company and the product/service it provides, there is a higher likelihood that their expectations will be met (Mahmoud et al., 2018). In other words, trust refers to the “willingness to rely on a partner in exchange (i.e., a reliable person who keeps promises)” (Ladhari & Michaud, 2015, p. 38). e-WOM, facilitated by consumer reviews and online communities, offers customers indirect insight into previous service experiences, helping them form beliefs or trust that the company will deliver high-quality service. (Sparks & Browning, 2011). According to Abubakar et al. (2017), tourists now favor other travelers’ opinions over traditional ads, which is why eWOM strongly shapes how they value a destination (Nofal et al., 2022; Roy et al., 2021).

Marić et al. (2017) emphasize that when it comes to eWOM, trust plays an important role and influences decisions, as the formal nature of written electronic words is generally perceived as more truthful, thereby affecting decision-making. It is important to note that potential consumers use online reviews from other users, which provide a wide range of information, as a strategy to minimize risk and uncertainty when making purchases (Chen, 2008; Ran et al., 2021).

In specific forms of tourism, such as medical tourism, there is a higher level of uncertainty and risk, so to gain a greater degree of trust, information is more frequently sought from previous users or experienced individuals (Ladhari & Michaud, 2015). Some research findings show the positive impact of e-WOM on trust (Abubakar & Ilkan, 2016). The study conducted by Ladhari and Michaud (2015) shows that positive feedback enhances the level of trust tourists have in a specific destination. They note that tourists are often inclined to trust comments and information left by other travelers on trusted websites on the Internet. Research conducted by Sofronijević and Kocić (2022) shows that online consumer reviews positively influence the purchase of tourist products. It is also important to mention that trust is a dimension that is not simple to analyze from the aspect of electronic interpersonal communication (Lončarić et al., 2016; Qiu et al., 2012), considering that not all websites offer information about the source, which prevents the assessment of its expertise (Lopez & Sicilia, 2014). According to a study by Jalilvand et al. (2012), trust plays a mediating role in the relationship between e-WOM and the intention to visit a destination. A study conducted by Qiu et al. (2022) confirmed that destination trust partially mediates the relationship between online review valence and travel intention. Consumer involvement level serves as a moderator (Park et al., 2007). Lujun et al. (2021) found that trust does not moderate the relationship between the frequency of online reviews and the intention to visit a specific destination. Based on the aforementioned, the following hypothesis can be defined:

H5: Trust has a moderating effect on the relationship between e-WOM and the intention to visit a destination.

3. Research methodology and sample structure

The research aims to explore how electronic interpersonal communication influences consumers’ intention to visit a destination and whether trust moderates this relationship.

The research was conducted in the Republic of Serbia between June and August 2024, with a sample of 128 respondents segmented by gender, age, education level, employment status, and income level. Data were collected through an online survey in which respondents rated their agreement with statements on a five-point Likert scale. The questionnaire included 29 statements, organized into five factors. The basis for selecting statements related to E-WOM comes from the research conducted by Lin et al., (2013). The statements related to the intention to visit a destination were taken from the study conducted by Mohamed et al. (2015). For the selection of statements related to the destination image, the study conducted by Harahap and Dwita (2012) was used. The statements concerning the variable attitude toward the destination were drawn from the study by Hsu et al. (2009), while the statements related to the variable of trust were adapted based on the research conducted by Zainal et al. (2017). The statements from relevant studies were adapted to create the survey questionnaire.

In the sample of 128 respondents, female respondents dominate (60.94%), while 51 respondents are male (39.48%). The largest number of respondents are between 25 and 40 years old (41.0%) and live in urban areas (65.62%). In terms of educational background, most respondents have a higher education degree (53.13%).

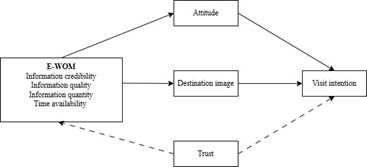

Data processing was conducted using the statistical software SPSS v20. A research model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research model

Source: Authors’ research

4. Results and discussion

Once the statements were grouped, a reliability analysis was carried out (Table 1). The Cronbach’s alpha values indicate that all factors demonstrate internal consistency, with each factor’s coefficient exceeding the 0.7 threshold. The “e-WOM” factor exhibits the highest internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.954, while the “Destination Image” factor shows the lowest internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.715.

Table 1: Results of the factor analysis

|

Factors |

Mean |

St. dev. |

Cronbach’ alpha |

|

E-WOM |

3.8432 |

0.8803 |

0.954 |

|

Destination image |

4.1074 |

0.6928 |

0.715 |

|

Attitude towards destination |

4.1172 |

0.7417 |

0.772 |

|

Trust |

4.1484 |

0.8489 |

0.863 |

|

Visit intention |

4.1133 |

0.7035 |

0.792 |

Source: Authors’ research

After the regression analysis, a correlation analysis was applied (Table 2). The values of Pearson’s correlation coefficient indicate a strong linear relationship between all pairs of variables. The results reveal that the most significant correlation is between the factors “Attitude toward the destination” and “e-WOM”, due to the highest Pearson correlation coefficient value of 0.877. The lowest Pearson coefficient value of 0.658 appears in the relationship between the factors “Destination Image” and “Trust”, indicating the lowest degree of correlation.

Table 2: Correlation matrix

|

Var. |

E-WOM |

D. image |

Attitude |

Trust |

V. intention |

|

E-WOM |

1 |

0.799** |

0.877** |

0.658** |

0.793 |

|

D. image |

0.779* |

1 |

0.704** |

0.649** |

0.761** |

|

Attitude |

0.877** |

0.704** |

1 |

0.908** |

0.762** |

|

Trust |

0.857** |

0.701** |

0.908** |

1 |

0.840** |

|

V. intention |

0.793** |

0.761** |

0.762** |

0.840** |

1 |

** The correlation coefficient is significant at the 0.01 level

Source: Authors’ research

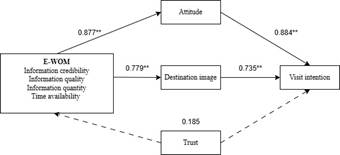

Results shown in Table 3, suggest that 77% of positive word-of-mouth is explained by the attitude towards the destination (R² = 0.770). This indicates that the regression model is suitable for analysis (R² > 0.5). The value of the β coefficient is 0.877 and is statistically significant (sig = 0.00 < 0.05).

Table 3: Simple regression analysis (dependent variable – Attitude towards destination)

|

Variable |

R2 |

β |

T |

|

E-WOM |

0.770 |

0.877 |

20.514 |

** The correlation coefficient is significant at the 0.00 level

Source: Authors’ research

According to the findings presented in Table 4, 60.7% of positive word-of-mouth is explained by the destination image (R² = 0.607), which suggests that the regression model is suitable for analysis (R² > 0.5). The value of the β coefficient is 0.779 and is statistically significant (sig = 0.00 < 0.05).

Table 4: Simple regression analysis (dependent variable – Destination image)

|

Variable |

R2 |

β |

T |

|

E-WOM |

0.607 |

0.779 |

13.964 |

** The correlation coefficient is significant at the 0.00 level

Source: Authors’ research

The data provided in Table 5, shows that 58% of the intention to visit the destination is explained by the attitude toward the destination (R² = 0.580), indicating that the regression model is suitable for analysis (R² > 0.5). The value of the β coefficient is 0.779 and is statistically significant at the sig = 0.00 level.

Table 5: Simple regression analysis (dependent variable – Visit intention)

|

Variable |

R2 |

β |

T |

|

Attitude towards destination |

0.580 |

0.884 |

17.671 |

** The correlation coefficient is significant at a 0.00 significance level

Source: Authors’ research

As evidenced by the data in Table 6, it can be concluded that 54% of the intention to visit the destination is explained by the attitude toward the destination (R² = 0.540), indicating that the regression model is suitable for analysis (R² > 0.5). The value of the β coefficient is 0.735 and is statistically significant at the sig = 0.00 level.

Table 6: Simple regression analysis (dependent variable – Visit intention)

|

Variable |

R2 |

β |

t |

|

Destination image |

0.540 |

0.735 |

12.172 |

** The correlation coefficient is significant at a 0.00 significance level.

Source: Authors’ research

After examining the main effects of the determinants, interaction effects were also determined. For this purpose, a moderation regression analysis, shown in Table 7, was conducted. The variable trust was used as the moderator. “A moderator can generally be defined as a quantitative or qualitative variable that influences the direction and/or strength of the relationship between the independent and dependent variable” (Baron & Kenny, 1986, p. 1174).

Table 7: Moderation regression analysis

|

Variables |

R2 |

β |

T |

Sig. |

|

E-WOM |

0,731 |

0,856 |

18,586 |

0,00 |

|

E-WOM*trust |

0,753 |

0,185 |

3,515 |

0,01 |

Dependent variable: Visit intention

Source: Authors’ research

Given the coefficient of determination (R² = 0.753), we conclude that the model explains 75.3% of the variability in the intention to visit a destination, which is statistically significant at the 0.01 level.

Figure 2: Research results

Source: Authors’ research

The moderation regression analysis shows a statistically significant moderation effect. Specifically, trust positively moderates the relationship between e-WOM and the intention to visit a destination, with a statistically significant effect (p = 0.01 < 0.05), as demonstrated by the positive β coefficient value (β = 0.785). This means that as trust increases, the relationship between e-WOM communication and the intention to visit a destination strengthens. Simple regression analysis results and iteration effects are presented in Figure 2.

5. Discussion

The results of a simple regression analysis show that e-WOM positively influences tourists’ attitudes toward a destination, thereby confirming the first hypothesis. In other words, positive recommendations, reviews, comments, and ratings shared online contribute to the formation of positive attitudes toward a particular destination. The results correspond with other studies that have demonstrated the impact of e-WOM communication on tourists’ attitudes (Chu et al., 2022; Jalilvand & Samiei, 2012; Lee & Cranage, 2012; Miao, 2015).

The analysis also found that attitudes toward a destination serve as an indicator of the intention to visit, which confirms the second hypothesis. This finding aligns with the research by Choirisa et al., 2021, Lee and Cranage (2014), Miao (2015) and Sparks and Browning (2011). These findings highlight the significance of fostering and sustaining positive attitudes toward a destination as a crucial factor in attracting visitors. In essence, the more favorable tourists’ attitudes are toward a destination, the greater the likelihood of their intention to visit.

According to the results of the regression analysis, electronic interpersonal communication is also linked to the image of the destination and influences it positively, thereby confirming the third hypothesis. The results indicate that communication through electronic channels such as social media, forums, blogs, and reviews can significantly shape the perception and image of a particular destination. When visitors share positive experiences and recommendations about a destination, it contributes to building a positive image of it in the minds of other potential visitors. These findings are consistent with the results of a study conducted by Hamouda and Yacoub (2018). On the other hand, Jalilvand and Heidary (2017) note that although e-WOM influences the image of a destination, non-electronic WOM communication has a stronger impact.

Furthermore, a simple regression analysis confirmed that the image of a destination positively influences the intention to visit a particular destination, confirming the fourth hypothesis. It can be said that consumers’ perception of a destination’s image, shaped through electronic communication channels, strengthens their intention to visit. Doosti et al. (2016) also emphasize that destination image significantly predicts consumer intention and can influence destination choice. In addition, Park and Nunkoo (2013) highlight that various dimensions of the image impact consumers’ intention to visit a particular tourist destination, aligning with the research results obtained.

A moderation regression analysis revealed that trust has a significant moderating effect, strengthening the relationship between electronic interpersonal communication and the intention to visit a destination, thus confirming the final, fifth hypothesis. In other words, when individuals have more trust in the sources of information received through electronic communication channels, this relationship becomes stronger. This supports the hypothesis that trust plays a key role in translating digital communication into decision-making, such as the decision to visit a destination. The results do not align with those obtained in the study conducted by Lujun et al. (2021). Studies by Andriani et al. (2019), Jamaludin et al. (2012) and Qiu et al. (2022) indicate that trust is a moderator in this relationship.

6. Conclusion

Word-of-mouth communication has always been a powerful marketing tool due to its influence on the perception of products and services. Today, technological advancements have transformed WOM into eWOM, enabling a broader and faster exchange of information via the Internet. eWOM offers numerous advantages, such as greater visibility and formality, but it also carries certain risks due to a lack of content control. In the tourism sector, eWOM has proven crucial in shaping tourist decisions, quickly becoming an indispensable source of information in modern tourism. This move from traditional to digital communication underscores the need to adapt strategies to meet modern consumer expectations.

The research presents several theoretical and practical implications. Firstly, it expands existing knowledge on interpersonal communication, both electronic and non-electronic, with an emphasis on the determinants through which it indirectly influences the intention to visit a tourist destination. The primary aim of the research is to determine the main effects and the moderating effect of trust in the relationship between electronic interpersonal communication and the intention to visit a tourist destination. The novelty of the paper lies in its focus on the increasingly significant concept of eWOM, which is far more modern in the tourism sector compared to traditional WOM, mainly due to modern communication and information methods, as well as its broad reach, visual element, and increased visibility. The primary contribution of the study is testing the moderating role of trust, given that, to the authors’ knowledge, few studies examine the moderating effect in similar models.

Regarding practical implications, the research showed that eWOM is a significant driver of tourists’ attitudes toward specific destinations. The findings highlight the importance of managing eWOM communication in strategies to promote a given destination. Positive reviews and recommendations through various online channels should be encouraged, while negative ones should be monitored and addressed to minimize their adverse effects on potential tourists’ attitudes. Consumers should be reminded to leave comments and reviews through notification systems via email or phone numbers, and incentives can be provided to encourage them to do so. It is also important to show concern for negative reviews, learn more about the causes of negative experiences, and encourage problem-solving.

The research shows that established attitudes influence the intention to visit a particular destination. Therefore, it is crucial to create and maintain positive attitudes toward the destination as a key factor in attracting visitors. Marketing and promotional activities should focus on creating positive associations and experiences related to the destination, as this can directly impact potential tourists’ decision to visit. Strategies such as showcasing positive stories, experiences of other tourists, and creating an emotional connection with the destination can contribute to forming favorable attitudes that encourage the intention to visit.

The research shows that a destination’s image has a strong positive impact on the intention to visit. Maintaining a good image can involve various strategies, including promotion through positive media campaigns, reviews, photos, firsthand stories, and experiences of previous visitors. Additionally, focusing on specific aspects of the image most attractive to the target group can be key to increasing interest and the intention to visit the destination. The results indicate that marketing strategies and promotional campaigns for tourist destinations should focus on building and strengthening trust among potential tourists. This can be accomplished through transparency, reliable sources of information, and authentic communication with potential tourists. Despite its contributions, this study has certain limitations. The primary limitation concerns the sample size and composition, given that the study was confined to Central Serbia and includes a relatively small respondent pool, limiting its representativeness. Secondly, the analysis included only electronic interpersonal communication, with both positive and negative communication considered together. The effects of the variables were assessed using a single dependent variable – the intention to visit the destination. Therefore, future research could expand the sample to include respondents from neighboring countries, enabling a comparative analysis with this study. Additionally, future research directions could involve comparative analysis of the effects of positive and negative eWOM or electronic and non-electronic word-of-mouth communication. It would also be possible to examine the impact of these determinants on tourist satisfaction and loyalty, with these factors serving as the dependent variable in the model. Furthermore, segmentation of respondents by educational or age structure could be performed to identify differences in satisfaction among users across various groups.

CRediT author statement

Julija Vidosavljević: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Supervision. Nađa Đurić: Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation.

Declaration of generative AI in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors did not use generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Abubakar, A. M., & Ilkan, M. (2016). Impact of online WOM on destination trust and intention to travel: A medical tourism perspective. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(3), 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.005

2. Ajzen, I. (2001). Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 27–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27

3. Alsheikh, D. H., Abd Aziz, N., & Alsheikh, L. H. (2021). The impact of electronic word of mouth on tourists visit intention to Saudi Arabia: Argument quality and source credibility as mediators. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 10(4), 1152–1168. https://doi.org/10.46222/ajhtl.19770720.154

4. Andriani, K., Fitri, A., & Yusri, A., (2019). Analyzing influence of electronic word of mouth (Ewom) towards visit intention with destination image as mediating variable: A study on domestic visitors of museum Angkut in Batu, Indonesia. Economics & Business, 1(19), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.18551/econeurasia.2019-01.07

5. Aprilia, F., & Kusumawati, A. (2021). Influence of electronic word of mouth on visitor’s interest to tourism destinations. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(2), 993–1003. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no2.0993

6. Baron, R., & Kenny, D. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

7. Chen, Y. (2008). Herd behavior in purchasing books online. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(5), 1977–1992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2007.08.004

8. Chi, C. G. Q., & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tourism Management, 29(4), 624–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.007

9. Choirisa, S. F., Purnamaningsih, P., & Alexandra, Y. (2021). The effect of e-WOM on destination image and attitude towards to the visit intention in Komodo national park, Indonesia. Journal of Tourism Destination and Attraction, 9(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.35814/tourism.v9i1.1876

10. Chu, Q., Bao, G., & Sun, J. (2022). Progress and prospects of destination image research in the last decade. Sustainability, 14(17), 10716. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su141710716

11. Chu, S-C., Lien , C-H., & Cao, Y. (2019). Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) on WeChat: Examining the influence of sense of belonging, need for self-enhancement, and consumer engagement on Chinese travelers’ eWOM. International Journal of Advertising, 38(1), 26–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2018.1470917

12. Deb, R., Kondasani, R. K. R., & Das, A. (2024). Package adventure tourism motivation: Scale development and validation. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2024.2343632

13. Doosti, S., Jalilvand, M. R., Asadi, A., Khazaei Pool, J., & Mehrani Adl, P. (2016). Analyzing the influence of electronic word of mouth on visit intention: The mediating role of tourists’ attitude and city image. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 2(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-12-2015-0031

14. Filipović, J., Šapić, S., & Dlačić, J. (2023). Social media and corporate image as determinants of global and local brands purchase: Moderating effects of consumer openness to foreign cultures. Hotel and Tourism Management, 11(1), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.5937/menhottur2301079F

15. Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Boston: Addison-Wesley

16. Girish, P., Sameer, H., & Giacomo, D. C. (2017). Understanding the relationships between tourists emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515620567

17. Goyal, C., & Taneja, U. (2023). Electronic word of mouth for the choice of wellness tourism destination image and the moderating role of COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Tourism Futures. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-08-2022-0207

19. Hamouda, M., & Yacoub, I. (2018). Explaining visit intention involving eWOM, perceived risk motivations and destination image. International Journal of Leisure and Tourism Marketing (IJLTM), 6(1), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLTM.2018.089236

20. Harahap, S. M., & Dwita, V. (2020). Effect of EWOM on revisit intention: Attitude and destination image as mediation variables (Study in Pasaman Regency Tourism Destinations). Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, 152, Proceedings of the 5th Padang International Conference On Economics Education, Economics, Business and Management, Accounting and Entrepreneurship (PICEEBA-5 2020). https://doi.org/10.2991/aebmr.k.201126.067

21. Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., Walsh, G., & Gremler, D. D. (2004). Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.10073

22. Hsu, C. H. C., Cai, L. A., & Li, M. (2009). Expectation, motivation, and attitude: A tourist behavioral model. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 282–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509349266

23. Jalilvand, M. R., & Heidary, A. (2017). Comparing face-to-face and electronic word-of-mouth in destination image formation: The case of Iran. Information Technology & People, 30(4), 710–735. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-09-2016-0204

24. Jalilvand, M. R., & Samiei, N. (2012). The effect of electronic word of mouth on brand image and puruchase intention. An empirical study in the automobile industry in Iran. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 30(4), 460–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348012451455

25. Jalilvand, M. R., Neda, S., Behrooz, D., & Parisa, Y. M. (2012). Examining the structural relationships of electronic word of mouth, destination image, tourist attitude toward destination and travel intention: An integrated approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1-2), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.001

26. Jamaludin, M., Johari, S., Aziz, A., Kayat, K., & Yusof, M. R. (2012). Examining structural relationship between destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty. International Journal of Independent Research and Studies, 1(3), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.007

27. Kim, H., & Lee, S. (2015). Impacts of city personality and image on revisit intention. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 1(1), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-08-2014-0004

28. Kocić, M., & Radaković, K. (2019). Implikacije elektronske interpersonalne komunikacije za izbor wellness ponude [The implications of the electronic word-of-mouth communication in choosing a wellness offer]. Ekonomski Horizonti, 21(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.5937/ekonhor1901043K

29. Ladhari, R., & Michaud, M. (2015). eWOM effects on hotel booking intentions, attitudes, trust, and website perceptions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 46, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.01.010

30. Lee, C. H., & Cranage, D. A. (2014). Toward understanding consumer processing of negative online word-of-mouth communication: The roles of opinion consensus and organizational response strategies. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 38(3), 330–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348012451455

32. Litvin, S. W., Goldsmith, R. E., & Pan, B. (2008). Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tourism Management, 29(3), 458–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.05.011

34. Lopez, M., & Sicilia, M. (2014). Determinations of E-WOM influence:The role of consumers’ internet experience. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 9(1), 28–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-18762014000100004

35. Lujun, S., Yang, Q., Swanson, S., & Chen, N. (2021). The impact of online reviews on destination trust and travel intention: The moderating role of online review trustworthiness. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 28(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/13567667211063207

36. Mahmoud, A., Hinson, R., & Maxwell, A. (2018). The effect of trust, commitment, and conflict handling on customer retention: The mediating role of customer satisfaction, Journal of Relationship Marketing, 17(6), 1–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15332667.2018.1440146

37. Marić, D., Kovač Žnideršić, R., Paskaš, N., Jevtić, J., & Kanjuga, Z. (2017). Modern consumer and electronic interpersonal communication. Marketing, 48(3), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.5937/Markt1703147M

38. Marić, D., Leković, K., & Džever, S. (2024). The impact of online recommendations on tourist’s decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Faculty of Economis in Subotica. https://doi.org/10.5937/AnEkSub2200012M

39. Marinković, V. & Kalinić, Z. (2017). Antecedents of customer satisfaction in mobile commerce: Exploring the moderating effect of customization. Online Information Review, 41(2), 138–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-11-2015-0364

40. Marinković, V., Senić, V., Obradović, S., & Šapić, S. (2012). Understanding antecedents of customer satisfaction and word-of-mouth communication: Evidence from hypermarket chains. African Journal of Business Management, 6(29), https://doi.org/8515-8524.10.5897/AJBM11.1455

41. Marković, I., Borisavljević, K., & Rabasović, B. (2024). The influence of destination image on the domestic tourists’ behavior. Marketing, 55(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.5937/mkng2402125M

42. Martini, E. (2022). Impact of e-WOM and WOM on destination image in shopping tourism business. JDM (Journal Dinamika Manajemen), 13(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.15294/jdm.v13i1.31819

43. Martın-Santana, J.D., Beerli-Palacio, A., & Nazzareno, P.A. (2017). Antecedents and consequences of destination image gap. Annals of Tourism Research, 62, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.11.001

45. Mirić, M., & Marinković, V. (2023). Perceived risk and travel motivation as determinants of outbound travel intention during the COVID–19 pandemic. Marketing, 54(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.5937/mkng2301017M

46. Mitić, S. (2020). Word of mouth on the Internet-Cross-cultural analysis. Marketing, 51(2), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.5937/markt2002088M

47. Mohamed, M., Aziz, Wael, A., Khalifa, Gamal, K., & Mayouf, Magdy, M. (2015). Determinants of electronic word of mouth (EWOM) influence on hotel customers’ purchasing decision. Journal of Faculty of Tourism and Hotels, 9(2), 194–223.

48. Nielsen annual marketing report (2023). Retrieved September 10, 2024 from https://www.nielsen.com/insights/2023/need-for-consistent-measurement-2023-nielsen-annual-marketing-report/

49. Nofal, R., Bayram, P., Emeagwali, O. L., & Al-Mu’ani, L. (2022). The effect of eWOM source on purchase intention: The moderation role of weak-tie eWOM. Sustainability, 14(16), 9959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169959

50. Paisri, W., Ruanguttamanun, C., & Sujchaphong, N. (2022). Customer experience and commitment on eWOM and revisit intention: A case of Taladtongchom Thailand. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2108584. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2108584

51. Park, D. B., & Nunkoo, R. (2013). Relationship between destination image and loyalty: Developing cooperative branding for rural destinations. 3rd International Conference on International Trade and Investment, University of Mauritius.

52. Park, D.-H., Lee, J., & Han, I. (2007). The effect of on-line consumer reviews on consumer purchasing intention: The moderating role of involvement. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 11(4), 125–148. https://doi.org/10.2753/jec1086-4415110405

53. Pham, T., Le, T., Thi, K., Nguyen, T., & Tran, T. (2025). Unveiling the impacts of eWOM on tourist revisit intention from a cognitive perspective: The moderating role of trade-offs. Cogent Business & Management. 12(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2025.2452239

54. Philips, W. J., Wolfe, K., Hodur, N., & Leistritz, F. L. (2013). Tourist word-of-mouth and revisit intentions to rural tourism destinations: A case of North Dakota, USA. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.879

55. Qiu, L., Pang, J., & Li, K. H. (2012). Effects of conflicting aggregated rating on eWOM review credibility and diagnosticity: The moderating role of review valence. Decision Support Systems, 54(1), 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.08.020

56. Ran, L., Zhenpeng, L., Bilgihan, A., & Okumus, F. (2021). Marketing China to US Travelers through electronic word-of-mouth and destination image: Taking Beijing as an example. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766720987869

57. Roy, G., Datta, B., Mukherjee, S., & Basu, R. (2020). Effect of eWOM stimuli and eWOM response on perceived service quality and online recommendation. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(4), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1809822

59. Seow, A. N., Foroughi, B., & Choong, Y. O. (2024). Tourists’ satisfaction, experience, and revisit intention for wellness tourism: E word-of-mouth as the mediator. Sage Open, 14(3), 21582440241274049. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241274049

60. Sharipudin, M.-N. S., Cheung, M. L., De Oliveira, M. J., & Solyom, A. (2023). The role of post-stay evaluation on eWOM and hotel revisit intention among Gen Y. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(1), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/10963480211019847

61. Social Serbia (2024). Social Serbia. Retrieved September 15, 2024 from https://pioniri.com/sr/social-serbia-2024-objavljeni-najnoviji-podaci/

62. Sofronijević, K., & Kocić, M. (2022). The determinants of the usefulness of online reviews in the tourist offer selection. Hotel and Tourism Management, 10(2), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.5937/menhottur2202025S

63. Sparks, B. A., & Browning, V. (2011). The impact of online reviews on hotel booking intentions and perception of trust. Tourism Management, 32(6), 1310–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.12.011

64. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (2023). Usage of information and communication technologies in the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved September 10, 2024 from https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2023/PdfE/G202316018.pdf

65. Sweeney, J. C., Soutar, G. N., & Mazzarol, T. (2008). Factors influencing word of mouth effectiveness: Receiver perspectives. European Journal of Marketing, 42(3/4), 344–364. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560810852977

66. Teng, S., Khong, K. W., Goh W. W., & Chong, A. (2014). Examining the antecedents of persuasive eWOM messages in social media. Online Information Review, 38(6), 746–768. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-04-2014-0089

67. Yan, Q., Zhou, S., & Wu, S. (2018). The influences of tourists’ emotions on the selection of electronic word of mouth platforms. Tourism Management, 66, 348–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.12.015

68. Yang, W., & Mattila, A. S. (2017). The impact of status seeking on consumers’ word of mouth and product preference – A comparison between luxury hospitality services and luxury goods. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 41(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348013515920

69. Yang, X., Mohammad, J., & Quoquab, F. (2024). A study of cultural distance, eWOM and perceived risk in shaping higher education students’ destination image and future travel plan. Journal of Tourism Futures, 10(2), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-03-2023-0080

70. Ye, Q., Law, R., Gu, B., & Chen, W. (2011). The influence of user-generated content on traveler behavior: An empirical investigation on the effects of e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 634–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.04.014

71. Yoo, K. H., & Gretzel, U. (2011). Influence of personality on travel-related consumer-Generated media creation. Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 609–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.05.002

72. Zainal, N. T. A., Harun, A., & Lily, J. (2017). Examining the mediating effect of attitude towards electronic words-of mouth (eWOM) on the relation between the trust in eWOM source and intention to follow eWOM among Malaysian travelers. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22(1), 35–44, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2016.10.004

73. Zarrad, H., & Debabi, M. (2015). Analyzing the effect of electronic word of mouth on tourists’ attitude toward destination and travel intention. International Research Journal of Social Sciences, 4(4), 53–60.