Source: Own processing

| Original Scientific Paper | UDC: 338.486.23(437.6) |

Iveta Fodranová1*, Mária Puškelová1, Katarína Mrkvová2, Branislav Dudić3*

1 University of Economics in Bratislava, Faculty of Commerce, Department of Services and Tourism, Bratislava, Slovakia

2College of Business and Hotel Management, Brno, Czech Republic

3Comenius University, Faculty of Management, Bratislava, Slovakia and University Business Academy, Faculty of Economics and Engineering Management, Novi Sad, Serbia

Abstract: Tour operators play a central role in the tourism industry. For tourism distribution channels, the emergence of new ones has been of particular significance, since it leads to priorities change in terms of distribution. The purpose of the current study was to examine the Slovak incoming tour operators in relation to tourism distribution in a highly competitive environment. The findings show that the Slovak incoming tour operators as a mediator of accommodation services are not the first choice of a foreign customer when it comes to accommodation provision. This is the consequence of the fact that tour operators are not able to compete in an adequate way with electronics distribution channels (e.g. Booking, Trivago, Go global and others). The research results show that the Slovak incoming tour operators are not able to develop their activities concerning booking offer. If they want to survive, they will have to change their traditional business model and structure their product portfolio and focus on offer of new different services and dynamic products.

Keywords: tour operator, tourism distribution channel, accommodation services

JEL classification: Z32, L83, L84

Perspektive receptivnih turoperatora u visoko konkurentnom okruženju - slučaj Slovačke

Sažetak: Turoperatori imaju centralnu ulogu u turističkoj delatnosti. Od posebnog značaja za kanale distribucije u turizmu je pojava novih kanala što dovodi do promena prioriteta u smislu distribucije. Svrha studije bila je ispitati slovačke turoperatore u vezi sa turističkom distribucijom u visoko konkurentnom okruženju. Rezultati pokazuju da slovački turistički operateri kao posrednici usluga smeštaja nisu glavni izbor stranog turiste kada je u pitanju usluga smeštaja. To je rezultat činjenice da turoperatori nisu u mogućnosti da se u dovoljnoj meri nadmeću sa elektronskim kanalima distribucije (npr. Booking, Trivago, Go global i drugi). Rezultati istraživanja su pokazali da slovački receptivni turoperatori ne mogu izgraditi svoje aktivnosti u vezi sa ponudom usluga rezervacije. U slučaju da žele da opstanu, moraju da promene svoj tradicionalni poslovni model i strukturiraju svoj portfolio proizvoda i fokusiraju se na ponudu novih različitih usluga i dinamičnih proizvoda.

Ključne reči: turoperator, turistički distributivni kanal, usluge smeštaja

JEL klasifikacija: Z32, L83, L84

1. Introduction

The travel industry is highly structured, and businesses within the industry tend to specialize in one or a small number of functions driven by their core business (Saffery et al., 2007). One of the most critical elements is distribution channels. Tourism distribution channels are usually associated with travel agencies (Ivanov & Zhechev, 2011) which include tour operators and travel agents. A tour operator enters a distribution process as an intermediary (Sheldon, 1986). They liaise with several organizations to design packages and sell them to tourists at a single price (Tepelus & Córdoba, 2005; Khairat & Maher, 2012). According to Pileliené and Šimkus (2012), the tour operator is the principal service provider in the tourism industry, responsible for the provision of promised service package, fulfilling commitments, and constant control through the whole period of service provision. The tour operators arrange standard as well as customized tour packages to meet the customer demand (Bhatia, 2014).

Several studies have explored a tour operator as the main service provider. “It is responsible for delivering and/or concluding contracts and monitoring the promised mix of services, including all measures related to tickets, transport, accommodation, tours, guiding services throughout the service period" (Atilgan et al., 2003, 4). Holloway and Humphreys (2012) define a tour operator as a company that individually purchases product components such as transportation, accommodation and other services and combines them into a package that can be sold directly or indirectly to the customer. Singh (2008) states that a tour operator is a business that deals with the sale of travel that are based on products and services. According to Jeeva and Tran (2014), tour operator can also be viewed as wholesalers in the tourism distribution channels. They play the role of professional sources of information for customers; and tourists tend to rely on these intermediaries for information about tour packages (Alamdari, 2002; Bieger & Laesser, 2004).

Tour operators focus on either domestic or outbound travel tourism in the context of creating travel offers. According to the UN World Trade Organization, there are three kinds of tours – outbound, domestic and inbound - and consequently three types of tour operators. The first group consists of outgoing tour operators (broadcasters) that cooperate with a variety of suppliers both at home and abroad. Suppliers operate mostly abroad in the foreign destination where the tour operator organizes the tour and where tour operator´s clients are heading. The second group of tour operators is domestic ones that run trips and sightseeing to a domestic participant in the national territory. From the accounting perspective, the cash flows of a company can be summarized in the cash flow statement in three sections: operating activities, investment activities and financing activities (Knežević et al., 2018). The third group is incoming tour operators (receiving) that prepare and organize the offer of services in the destination where they operate. These offices fulfill a recipe function based on a specific market feature - to displace the offer from demand. Inbound tour operators (ITOs), on the contrary, are based at a destination and have expert knowledge of the destination (Mayaka & King, 2002; Budeanu, 2005; Akama & Kieti, 2007).

The relationships between incoming and outgoing tour operators are characterized by interconnectedness and reciprocal influence. The incoming tour operator can thus influence its suppliers (UNEP, 2014). Theobald (1998) states that some outgoing tour operators may influence or at least partially operate on their local partners in terms of implementing different quality standards in providing quality service or employing the workforce. The incoming tour operator plays a key role in the distribution channel.

An incoming tour operator organizes local transfers or city tours faster and is more flexible based on the requirements of a foreign tour operator. An important role is the knowledge of local language and cultural backgrounds. Buhalis and Laws (2004) state that an important aspect is the ability of the incoming tour operator to represent their destination internationally. Horster (2014) states that during presenting products and establishing contacts with potential clients (foreign outgoing tour operators), it is necessary to think about the typology of final clients with regard to the possible length of stay. Depending on the length of stay, the tour operator defines the product and territorial portfolios. The selection of destination, either short or long haul, determines various factors such as economic, socio-cultural, environmental and political (Horster, 2014). According to Block (2014), the primary motivation for holiday planning is the choice of a destination.

The main aim of this research was to examine the Slovak incoming tour operators in relation to tourism distribution in a highly competitive environment. The specific objectives were testing the relationship between (1) booking and source markets, and (2) class of accommodation provider and the source market.

2. Research methodology

The aim of the study was to examine the adoption of incoming tour operators to highly competitive environment. We have analyzed the distribution channels that the foreign clients used to book accommodation facilities. The traditional business model of the Slovak incoming tour operators predominantly consisted in providing accommodation. If the traditional model persists, which means that the Slovak incoming tour operators would book accommodation for visitors, then this relationship has to be manifested within the tested variables.

H1: There is a correlation between hotel booking and source market

H2: There is a correlation between hotel rate and source market.

If there is the absence of dependence between the monitored variables (accepting the hypothesis H0), it will imply that the traditional role of the incoming tour operators in the distribution channel has changed and other activities have become the dominant source of profit for the incoming tour operators. The object of the current study is the Slovak incoming tour operators, their entries and activities in the international market.

Data collection: Data for this study were collected from multiple sources, including primary data and secondary data. Primary data collection took place during five months in the year 2015 in the accommodation facilities of three self-governing regions with the highest number of overnight stays by foreign visitors – Bratislava, Žilina and Prešov Regions. The primary data were collected through the print semi-structured questionnaires distributed to the tour inbound operating companies. Altogether 201 of 2* to 5* accommodation facilities were addressed through the survey method, with 61% response rate (121 responses), out of which 44 hotels were in the Bratislava Region, 43 in the Žilina Region and 34 in the Prešov Region. The secondary data were gathered from the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. In the course of data analysis, quantitative research method was applied in the study. The acquired data were processed in IBM SPSS Statistics Standard computer application, Pearson’s chi-square test of the independence of quality indicators, with the related characteristics evaluating the intensity of the correlation in question - proved suitable for the given variables. The hypothesis were tested at the significance level α=0.05 (with 95% probability).

3. Study results and discussion

The international growth of inbound travels has been reflected in positive numbers in the Slovak inbound tourism as well. New transport connections with various source markets have contributed to the increase of the number of visitors in the Slovak Republic in 2015. Based on that, the country has encountered increased number of customers from some source markets (Riga – Poprad, Wizz Air, 2015; London – Poprad, Wizz Air, 2015; Kiev – Košice, ČSA, 2015; United Arab Emirates – Bratislava, Fly Dubai, 2015, etc.). The better accessibility of Slovakia to the foreign customers can be attributed to a better railway connection with the Czech Republic, in the form of schedule density increase. The entry of the third foreign railway transporter, Leo Express, operating on route between the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic has caused a decrease of transport fees. Quoting the report from the Slovak Tourism Agency (Slovenská agentúra pre cestovný ruch) from 2016, the increase in the number of visitors and overnight stays from foreign countries was aided by good viewing statistics of the www.slovakia.travel web site, offering the targeted campaigns under Google and YouTube, as well. The agency was efficient in advertising the fact that the Slovak Government was about to take presidency of the council of EU in the second half of 2016, which positively contributed to the promotion of the country and attracting potential foreign customers (Slovenská agentúra pre cestovný ruch, 2016). Table 1 illustrates structure and dynamics of foreign customer accommodation by the source market in the accommodation facilities in particular Slovak regions between 2012 and 2015.

Region |

Number of foreign overnights |

change % |

||||

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2014/2013 |

2015/2014 |

|

Bratislava |

1 073 480 |

1 193 611 |

1 059 758 |

1 392 198 |

-12.6 |

23.9 |

Žilina |

847 079 |

913 416 |

787 166 |

852 768 |

-16 |

7.7 |

Prešov |

689 843 |

738 318 |

670 460 |

715 084 |

-10.1 |

6.2 |

Source: Own processing on the basis of data Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic

In 2014, a decrease of number of visitors and overnight stays in Slovakia (compared to 2013) was due to multiple reasons. One of those having negative consequences on the international inbound travels was the fact that within the foreign customer structure there were citizens of countries not using the euro (the Czech Republic, Poland, Ukraine, Hungary, the Russian Federation, the USA) (Slovenská Národná Banka, 2015; Slovenská agentúra pre cestovný ruch, 2016). In 2014 the exchange rate of euro to Hungarian forint, Ukrainian hryvna, Russian ruble, Czech koruna and US dollar have fluctuated (Slovenska Národná banka, 2015). This weakened the purchase power in primary source markets. Devaluation of these currencies made overnight stays in the Slovak Republic more expensive. Decrease in the number of the customers is indirectly linked to the persisting instability in Ukraine. This may have caused feelings of insecurity and unwillingness of the potential Western European and overseas customers to visit the country that is neighboring the one with unrests (in this case Slovakia). Aside of these factors, the development of tourism was affected by the weather as well. Ski resorts of the lower altitudes without artificial snowmaking suffered insufficient snowfall. Cold and rainy summer was not suitable for mountaineering and at the end of the day caused overall decline in the number of visitors to Slovakia (Slovenská agentúra pre cestovný ruch, 2016). In 2015, almost every part of the world reports increase in the international inbound travels, which was positively reflected in Slovakia, too. The three mentioned regions – Bratislava, Žilina, Prešov - remained steadily attractive to foreign customers.

In Table 2, 3 and 4 we did not want to provide information about market source in each class of the hotel (3, 4, 5*) for simple reason - Slovakia is small and each of the three regions (Bratislava, Žilina, Prešov) is also small, thus we found more suitable to display provided information on a bigger sample (i.e. 3 + 4 + 5* hotels).

Table 2: Overnight structure and dynamics of foreign clients in Bratislava Region according to source market in 2012-2015

No. |

Region |

Number of overnights |

change % |

||||

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2014/2013 |

2015/2014 |

||

1 |

Czech Republic |

204 538 |

202 342 |

187 195 |

226 377 |

-7.5 |

20.9 |

2 |

Germany |

102 835 |

126 068 |

113 917 |

144 087 |

-9.6 |

26.5 |

3 |

United Kingdom |

61 773 |

66 505 |

55 358 |

95 027 |

-16.8 |

71.7 |

4 |

Austria |

54 837 |

63 285 |

62 731 |

77 262 |

-0.9 |

23.2 |

5 |

Italy |

55 680 |

61 559 |

56 888 |

72 373 |

-7.6 |

27.2 |

6 |

Poland |

62 751 |

65 633 |

66 665 |

70 113 |

1.6 |

5.2 |

7 |

United States |

20 690 |

42 480 |

35 108 |

51 542 |

-17.4 |

46.8 |

8 |

France |

35 319 |

37 425 |

28 538 |

38 152 |

-23.7 |

33.7 |

9 |

Ukraine |

20487 |

48 327 |

31 797 |

36 327 |

-34.2 |

14.2 |

10 |

Hungary |

26 603 |

28562 |

28 102 |

31 850 |

-1.6 |

13.3 |

Source: Own processing on the basis of data Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic

Table 2 mentions the USA as a source country and Table 3 provides data on an Asian country. Other countries from Asia are not mentioned for simple reason. There were not too many guests from those countries to fit in the provided scope. We asked hotels who (which nationality) stayed overnight in their hotel. 10 most frequent nationalities were evaluated = market sources that were put in the top 10 in the table. The same was done in Table 3 and Table 4. Those three tables provide the data on the country of origin of the most clients. We did research in 3*, 4* and 5* hotels.

Table 3: Overnight structure and dynamics of foreign clients in Žilina Region according to source market in 2012-2015

No. |

Country |

Number of overnights |

change % |

||||

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2014/2013 |

2015/2014 |

||

1 |

Czech Republic |

397 100 |

398 542 |

330 124 |

387 495 |

-17.2 |

17.4 |

2 |

Poland |

179 855 |

195 751 |

173 634 |

183 588 |

-11.3 |

5.7 |

3 |

Ukraine |

37 561 |

73 690 |

63 264 |

40 349 |

-14.1 |

-36.2 |

4 |

Russia |

33 723 |

46 516 |

36 009 |

21 600 |

-22.6 |

-40.0 |

5 |

Germany |

35 277 |

31 821 |

30 231 |

36 099 |

-5.0 |

19.4 |

6 |

Hungary |

16 873 |

19 951 |

16 346 |

22 777 |

-18.1 |

39.3 |

7 |

Lithuania |

12 482 |

14 311 |

15 835 |

13 751 |

10.6 |

-13.2 |

8 |

South Korea |

29 133 |

13 915 |

9 759 |

9 486 |

-29.9 |

-2.8 |

9 |

Romania |

9 429 |

8 097 |

9 020 |

9 223 |

11.4 |

2.3 |

10 |

United Kingdom |

7 030 |

8 375 |

6 834 |

8 733 |

-18.4 |

27.8 |

Source: Own processing on the basis of data Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic

Table 4: Overnight structure and dynamics of foreign clients in Prešov Region according to source market in 2012-2015

No. |

Region |

Number of foreign overnights |

change % |

||||

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2014/2013 |

2015/2014 |

|

1 |

Czech Republic |

265 747 |

264 219 |

231 224 |

274 088 |

-12.5 |

18.5 |

2 |

Poland |

118 361 |

110 402 |

102 695 |

101 212 |

-7.0 |

-1.4 |

3 |

Germany |

59 190 |

64 454 |

55 878 |

62 029 |

-13.3 |

11.0 |

4 |

Ukraine |

40 214 |

84 730 |

66 086 |

47 674 |

-22.0 |

-27.9 |

5 |

Hungary |

31 020 |

32 684 |

31 867 |

39 240 |

-2.5 |

23.1 |

6 |

Belorussia |

6 074 |

9 074 |

28 652 |

25 497 |

215.8 |

-11.0 |

7 |

Austria |

14 337 |

13 687 |

10 945 |

13 963 |

-20.0 |

27.6 |

8 |

Russia |

30 628 |

35 369 |

24 099 |

12 412 |

-31.9 |

-48.5 |

9 |

Lithuania |

10 069 |

11 486 |

11 160 |

11 193 |

-2.8 |

0.3 |

10 |

United Kingdom |

8 492 |

8 944 |

7 674 |

11 087 |

-14.2 |

44.5 |

Source: Own processing on the basis of data Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic

The abovementioned tables show a decrease in the number of visitors in 2014 (in percent) almost in all source markets. In 2015, Slovakia experienced decline in the number of arrivals of Ukrainian and Russian customers. Among the main reasons we can list is the devaluation of Russian and Ukrainian currency and trouble with obtaining a Slovak visa.

Slovakia has no database of incoming tour operators. In order to create a functional database we have employed methodology with classifying criteria that estimated the number of incoming tour operators and their links to the accommodation facilities in the destinations that they book for their customers – home-based incoming or foreign outgoing tour operators or companies. The results of the study show that the greatest volume of accommodation services was ordered by these tour operators: Satur (Bratislava) – 25.6 %

Aside of the already mentioned incoming tour operators, other tour operators cooperate with hotels as well. The form of their cooperation with the hotels varies from region to region. Some tour operators (e.g. Ostour, Fatra Travel or Tatra Travel) prefer cooperation with accommodation facilities located in the region of tour operator’s activity. The outcomes of the research show that e.g. the tour operator specialized in spa breaks – Sunflower – cooperates mostly with spa and wellness hotels. To the contrary, the biggest tour operator in Slovakia – Satur travel – cooperates with business hotels to a large extent. Hotels situated mostly around ski resorts report cooperation with tour operators such as Lino, Fatra travel or Liptour.

Figure 1: The incoming tour operator that cooperates with accommodation providers in the chosen Slovak regions in 2014

Source: Own processing

Chart 1 shows that Slovak tour operators provided accommodation in 3* and 4* hotels - more than 260 times. The least interest was shown for 5* hotels. These data imply that requests for accommodation in:

Based on the results of the research, we can state that in the facilities that we have addressed, the incoming tour operators are not the main purchasing agent of the accommodation for the foreign customers. In Bratislava Region 20.8 % of hotels do not receive orders from them. In Žilina Region this number reaches 27.8 % of hotels, while in Prešov Region it is 15.3 % of hotels. Study also shows that the individual customers contact the accommodation facility without mediation from the incoming tour operators. Out of 121 accommodation facilities in research:

a) Up to 81.82% of the total number of orders is received via electronic distribution channels (booking.com, HRS, Go global, etc.).

b) 18.2% of the orders were facilitated in other forms (directly via tour operator or eventually via hotel booking system).

If a foreign customer does not use incoming tour operator, he manages the booking:

The ratio of the use of different means of booking per accommodation facility in three regions included in the research was uneven. The electronic distribution channels prevail and so the order placement via incoming tour operators plays a secondary role. Despite this, we can state that it is not insignificant and it plays important role in the booking style of foreign customers. Statistic data of the processed results demonstrate the relation between method of booking / source market and a hotel rate / source market. The following analysis employs Pearson’s chi-square test of the independence of quality indicators with the related characteristics evaluating the intensity of the correlation in question (if the statistically significant correlation was confirmed).

There follow the acquired numbers of customers in particular source markets per particular way of booking:

Table 5: Observed frequencies ()

Booking |

Source market |

∑ |

||

Asia |

Europe |

USA |

||

Direct booking by foreign outgoing tour operator |

3.32 |

130.37 |

3.32 |

137 |

Booking by Slovak incoming tour operator |

5.72 |

224.57 |

5.72 |

236 |

Direct booking from corporate customer in Slovakia |

5.67 |

222.67 |

5.67 |

234 |

Direct booking from foreign corporate customer |

5.04 |

197.93 |

5.04 |

208 |

Direct booking via e-mail or hotel's website |

8.45 |

332.10 |

8.45 |

349 |

Direct booking via elec. distribution channels |

8.81 |

346.37 |

8.81 |

364 |

Sum |

37 |

1 454 |

37 |

1 528 |

Source: Own processing

Chi-squared Test is valid, provided 80% or more of Eij ≥ 5. 7

Table 6: Expected frequencies ()

Booking |

Source market |

∑ |

||

Asia |

Europe |

USA |

||

Direct booking by foreign outgoing tour operator |

0.85 |

0.087 |

0.85 |

1.79 |

Booking by Slovak incoming tour operator |

0.08 |

0.001 |

0.01 |

0.10 |

Direct booking from corporate customer in Slovakia |

0.02 |

0 |

0.07 |

0.10 |

Direct booking from foreign corporate customer |

0.76 |

0.004 |

0.21 |

0.98 |

Direct booking via e-mail or hotel´s website |

1.4 |

0.025 |

0.03 |

1.47 |

Direct booking via elec. distribution channels |

0 |

0.001 |

0.07 |

0.08 |

Sum |

3.14 |

0.12 |

1.27 |

4.53 |

Source: Own processing

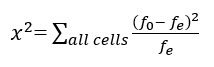

The Chi-Square test statistic is:

(1)

(1)

where:

= observed frequency in a particular cell

= expected frequency in a particular cell if is true

df = degree of freedom

x2= 4.530

df = (r – 1)(c – 1) = 10

x2 = 4.530 < x20,005 = 18. 307 ⇒ we accept H0

At the significance level α=0.05, we could not confirm statistically significant correlation between method of booking of the hotel and the source market which means that currently there is no statistically significant correlation between the method of booking a hotel in Slovakia and the source market.

In the following part, a relation between hotel rate and source market of the customers was evaluated. Chi-square test of the independence of quality indicators with the related characteristics evaluating the intensity of the correlation in question (if the statistically significant correlation was confirmed) was used. The second statistic hypothesis was tested at the significance level α=0.05 (with 95% probability).

The same methodology is employed for the data presented in Table 7, 8 and 9. However, all answers from the research (all information provided from the hotels) are summed. The number of users was not divided according to particular market sources, but rather summarized according to where they came from - Europe, Asia and the USA.

There follows the acquired number of visitors from the particular source markets in the particular hotel rate:

Table 7: Observed frequencies ()

Hotel rate |

Source market |

∑ |

||

Asia |

Europe |

USA |

||

3* |

0.58 |

43.09 |

2.33 |

46 |

4* |

0.35 |

26.23 |

1.42 |

28 |

5* |

0.06 |

4.68 |

0.25 |

5 |

Sum |

1 |

74 |

4 |

79 |

Source: Own processing

Table 8: Expected frequencies ()

Hotel rate |

Source market |

∑ |

||

Asia |

Europe |

USA |

||

3* |

0.58 |

0.09 |

0.76 |

1.43 |

4* |

1.18 |

0.06 |

0.24 |

1.47 |

5* |

0.06 |

0.10 |

2.20 |

2.37 |

Sum |

1.82 |

0.24 |

3.20 |

5.26 |

Source: Own processing

x2 = 5. 2642

df = (r – 1)(c – 1) = 10

x2 = 5. 2642 < x20,005= 9.488 ⇒ we accept H0

At the significance level α=0.05, we could not confirm statistically significant correlation between the hotel rate and source market of the customers.

In the traditional model, the incoming Slovak tour operator negotiated with suppliers (accommodation) at the destination and received a discount. The results of the research showed that the common way of booking is direct one via electronic distribution channels regardless of source market or hotel rate. There is no special relevant segment of clients or special relevant source market which should require booking via Slovak tour operators. In presence, incoming Slovak tour operators are not able to generate relevant profit from the service. However, the loss of this income should be a motivation for development of a new marketing strategy with emphasis on customization, specialization, active presence on social media and investments in information technology.

4. Conclusion

The results of the realized primary research suggest the following conclusions: the Slovak incoming tour operators have no significant influence in the mediation of the booking of accommodation for foreign customers. Advancements in technology had particularly high effects onto the way the tourism and hospitality industry operates (Kapiki, 2012; Scaglione et al., 2013). The entire industry shifted from traditional computer reservation systems to global distribution systems and finally towards the Internet age resulting in the emergence of online travel agencies (OTAs) such as Expedia, Orbitz, and Priceline (Inversini & Masiero, 2014). Foreign customers make booking mostly via world-wide electronic distribution channels. This is due to the simplicity of reservation that is conditioned by the existence of multi-lingual versions of the web-sites of the accommodation facilities and the customer reviews of these accommodation facilities. That means that the incoming tour operator cannot significantly compete with electronic distribution channels (e.g. Booking, Trivago, Go global and others) that have an advantage of world-wide coverage with unified web-site look and structure in each particular country. As a result, the Slovak incoming tour operators cannot primarily focus on mediating the booking of the accommodation services. New information and communication technologies shift the power of market players (Berne et al., 2012). This decreases their overall dependence on travel agencies and even makes them the stronger party in negotiations (Ivanov et al., 2015). Specific role in providing accommodation services is seen in booking accommodation for the customers from the source market that are obliged to have a visa upon arrival in Slovakia. In this case, the incoming tour operator deals with the formal requirements, so it is easier for the foreign customers to direct their requirements towards the operator (granting of the visa in Slovakia is conditioned by booking of the accommodation in the majority of cases). Therefore, they can ensure their access to the country much easier through the tour operator. The results do not show a correlation between hotel booking and source market as much as any correlation between hotel rate and source market which implies that the profiling of the segments by booking preference or hotel rate has no importance at this moment.

In current turbulent times, it is difficult for tour operators to maintain their position in the market. This is due to the continuously increasing globalization and more sophisticated information technology systems. On the other hand, this is also due to various economical and non-economical fluctuations that enormously increase competition not only among the enterprises but also among the majority of the destinations that are and may become attractive for any type of visitors. A way that the tour operator can address this situation is to prepare and subsequently offer complementary additional services related to the accommodation, i.e. offer an attractive complex quality product package.

Staying competitive in this industry requires continuous creativity to find innovative ways to attract new customers. Tour operators must be actively present on social media, which can help create brand awareness cost-effectively while engaging with the target audience. A customer must be always in the centre of their activity.

A future research direction should focus on whether the orientation of changes in consumer behavior has a significant effect on travel intentions, demand and expenditures. Another important stream of research should concentrate on the development of powerful digital marketing platform from which companies can actively promote relevant goods and services to create new opportunities for revenue growth.

4.1. Research limitations

The two most important limitations were found. There is no a reliable verified and classified system that could allow to expressly identify the Slovak incoming tour operators. The second limitation concerns unwillingness of some tour operators to participate in the research.

References

Received: 19 February 2019; Sent for revision: 11 March 2019; Accepted: 20 May 2019