| Original Scientific Paper | UDC: 338.48-6:502/504(569.3) |

Jad Abou Arrage1*, Suzanne Abdel Hady1

1Lebanese University, Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management, Beirut, Lebanon

*jadarrage@gmail.com

**Paper was presented at the Fourth International Scientific Conference "TOURISM IN FUNCTION OF DEVELOPMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA - Тourism as a Generator of Employment" held at the Faculty of Hotel Management and Tourism in Vrnjaĉka Banja, May 30th – June 1st, 2019

Abstract: Doubts exist about the ability of ecotourism to make tangible contributions to sustainable development. Despite the doubts ambiguity, ecotourism is closely related to sustainability. This paper aims to study the contribution of ecotourism to sustainable development in Lebanon from a market perspective. In order to assess the level of understanding of the ecotourism concept by the Lebanese nature-based tour operators and their contribution to sustainable development, field data related to their profile and practices was collected using a survey administered to 50 operators. The main findings showed that their compliance with the international ecotourism principles and guidelines is weak and that they have a low level of specialization. However, despite this fact, ecotourism is trending in Lebanon and is providing rural areas with some economic benefits and opportunities without having a comprehensive contribution to ecological conservation and cultural preservation. Two decades after its emergence in Lebanon, ecotourism remains an unorganized sector.

Keywords: ecotourism, sustainable development, ecotourism practices, nature-based tour operators, Lebanon

JEL classification: Q01

Ekoturizam i održivost: Prakse libanskih organizatora putovanja čije je poslovanje zasnovano na prirodi

Sažetak: Postoje sumnje u sposobnost ekoturizma da obezbedi opipljiv doprinos održivom razvoju. Uprkos ovoj sumnji, ekoturizam je usko povezan sa održivošću. Ovaj rad ima za cilj da prouči doprinos ekoturizma održivom razvoju u Libanu sa tržišne perspektive. Da bi se procenio nivo razumevanja koncepta ekoturizma od strane libanskih turoperatora čije je poslovanje zasnovano na prirodi, prikupljene su informacije putem ankete u kojoj je učestvovalo 50 turoperatora o njihovom doprinosu održivom razvoju, kao i terenski podaci vezani za njihov profil i prakse koje primenjuju. Glavni rezultati su pokazali da je njihova usklađenost sa međunarodnim principima i smernicama ekoturizma slaba i da imaju nizak nivo specijalizacije. Međutim, uprkos toj činjenici, ekoturizam je u trendu u Libanu i pruža ruralnim područjima određene ekonomske koristi i mogućnosti bez sveobuhvatnog doprinosa ekološkoj konzervaciji i očuvanju kulture. Dve decenije nakon pojave ovog koncepta u Libanu, ekoturizam i dalje ostaje sektor koji nije u potpunosti organizovan.

Ključne reči: ekoturizam, održivi razvoj, prakse u ekoturizmu, organizatoru putovanja usmereni na prirodu, Liban

JEL klasifikacija: Q01

1. Introduction

In the last two decades, ecotourism has become widely popular and one of the most dramatic outcomes of the environmental movements in developing countries for its potential contribution to sustainable development. This nature-based tourism form incorporates principles that revolve around the concept of sustainability such as biodiversity conservation, environmental education, economic development, social inclusion, and cultural preservation.

Along with the development of the tourism industry, the growth of research on ecotourism increased as well (Yeo & Piper, 2011). Various writers categorized ecotourism as a subset of the bigger concept of sustainable tourism and linked it to other types of tourism, such as nature and adventure-based tourism (Cater, 2015). Ecotourism is nowadays seen as the fastest growing sub-component of tourism. It will cover 5% of the global holiday market by 2024. The growth of this niche market is related to the fact that tourists are demanding a more environmentally friendly experience (Das & Chatterjee, 2015). The main reason behind unfolding ecotourism’s potential in developing countries resides in its capacity to contribute to sustainable development (Browder & Rich, 2004). However, the true purpose of ecotourism was debated and criticized since its emergence, where some researchers (e.g., Wheeller, 1993; Drumm & Moore, 2005; Courvisanos & Jain, 2006) claim that ecotourism’s main purpose is misunderstood by many and is a matter of marketing. Moreover, people who abuse the concept of ecotourism attract conservation conscious tourists to nature-based tourism programs under the banner of ecotourism (Cobbinah, 2015).

The main purpose of this study is to understand if ecotourism is misinterpreted and misused by nature-based tour operators in Lebanon through the assessment of their awareness and specialization levels, and the compliance of their practices with international ecotourism guidelines. This paper aspires to help in distinguishing real “eco” tour operators from free riders who abuse the ecotourism concept to gain an additional market share. This differentiation could prevent tourists from eco-exploitation by offering them an opportunity to evaluate the genuine ecotourism service providers.

2. Ecotourism and sustainability

Despite the fact that there are no precise studies on the origins of ecotourism, there is an implicit reinforcement that the ideas behind this concept emerged in the 1970s following the concern over the misuse of natural resources. In the late 1980s, the sustainable development concept was integrated into the tourism industry and different alternative tourism forms, including ecotourism, appeared on the market (Fennel, 2009). The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) gave the most inclusive definition of ecotourism as “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and involves interpretation and education” (Mondino & Beery, 2018). However, ecotourism overlaps with other forms of tourism such as adventure tourism, agro-tourism, rural tourism, etc. (Leksakundilok, 2004). Fennell (2001) classified five common variables that aid in distinguishing ecotourism: 1) the natural environment; 2) education; 3) protection or conservation of resources; 4) preservation of culture; and 5) community benefits. Moreover, Fennel (2015) considers ecotourism as a sustainable form of natural resources-based tourism, focused on experiencing and gaining knowledge about nature.

An increasing number of critics argue that ecotourism might be good in theory but it can be harmful in practice, especially in countries that lack proper management and norms, and where legislation ignores the risk of natural resources over-exploitation. Other researchers claim that ecotourism may lead to the abuse of marginalized communities and the commercialization of native cultures (Barzekar et al., 2011; Dekhili & Achabou, 2015).

The overlap between the main principles of ecotourism and sustainable development is evident. Researchers state that sustainability may be present in each particular piece of literature related to ecotourism (Browder & Rich, 2004). Ecotourism is often perceived as an excellent tool for promoting sustainable development and is considered as an applicable way to conserve the natural environment and foster social and economic gains (Jalani, 2012; Houtte, 2015). Sustainability is not only considered a goal for ecotourism but essentially a tool for reaching that goal (Figure 1). Due to the difficulty in measuring sustainability, it is crucial to highlight sustainability as the purpose and not necessarily the outcome. Most importantly, the best way to improve ecotourism is to maintain the philosophy of sustainable development and to have the will to maximize the probability of positive effects while minimizing the negative ones (Browder & Rich, 2004).

Figure 1: Ecotourism and sustainability

Source: Ross & Wall, 1999

In spite of the fact that the information on ecotourism’s contribution to development is rich, there remain a lot of doubts and ambiguity, which requires more investigation in the matter of what ecotourism truly implies. While numerous issues related to ecotourism will keep on being disputed, consent on the guiding principles of ecotourism has turned out to be obvious and many nations’ development strategies have embraced ecotourism in their plans believing that it can be a promising tool to reach sustainable development (Browder & Rich, 2004). The existing literature on ecotourism presents few empirical studies that examine the characteristics of its operators. According to Burton (1998), there are few tour operators that can qualify for ecotourism in reference to environmentally responsible behavior. After they recognized their negative effects on ecotourism destinations, many “eco-tour operators” developed voluntary guidelines to help themselves in controlling their actions (Sirakaya & Uysal, 1997). Accordingly, in 1993 the guidelines for “real” eco-tour operators were published by The Ecotourism Society (Wood et al., 1999). Wood (2002) states that responsible eco-tour operators are those who are successful in working to foster well planned interactive learning experiences that primarily present small groups of travelers to new environments and cultures while decreasing the adverse impacts on the environment and guaranteeing the ways to preserve its resources. The following table summarizes the main ecotourism guidelines for the “eco-tour operators” (Table1).

Table 1: Ecotourism Guidelines for Nature-based Tour Operators

Source: Sirakaya & Uysal, 1997; Wood, 2002; Kiper 2013

In recent years, ecotourism has become a buzz word. In some ways this looks like the propensity of manufacturers to mark various items as Green or ecologically friendly. Thus, there has been an increase in launching publications in the travel industry with references such as an eco-tour, eco-travel, eco-vacation, eco-adventures, eco-expedition and, of course, ecotourism (Wight, 1993). Moreover, the term ecotourism is used differently around the world and does not often refer to an activity that is environmentally responsible. It can be used as a marketing pull factor to sell products that might cause environmental deterioration. Likewise, many tourism service providers label their products under the term “ecotourism” without in truth changing their approach and practices (Acott et al., 1998; Das & Chatterjee, 2015; Dekhili & Achabou, 2015). However, the idea behind ecotourism remains ineffectively comprehended and much mishandled, and despite its rising popularity, ecotourism practices are not seen as beneficial as they should be neither for preservation nor for local people (Das & Chatterjee, 2015). Many scholars contend that the absence of a reasonable definition and ambiguities that encompass the term ecotourism make it relatively insignificant (Weaver, 2001). Browder & Rich (2004) argues that ecotourism is widely used to portray anything related to nature or irrelevant to mass tourism. Moreover, the term is frequently abused or misunderstood in relation to the original meaning of the concept (Wight, 1993; Mosammam et al., 2016).

3. Ecotourism in Lebanon

Despite the small surface area of Lebanon (10,452 km2), the rich cultural and natural heritage, its varied landscapes, mild climate, and the strategic location on the eastern Mediterranean allow tourism to play a leading role in the Lebanese economy. Tourism constitutes a main source of income and employment; according to Blom Invest Bank (2018), it accounted for 19% of Lebanon’s GDP in 2017. However, the Lebanese tourism industry faces many challenges including political instability, low competitiveness, seasonality, and environmental degradation. In the last two decades, Lebanon’s tourism market recorded important fluctuations driven by internal and external factors. Lebanon has been severely affected by the assassination of his Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri in 2005, the war with Israel in 2006, internal political instability in 2008, and the influx of Syrian refugees since 2011. According to the Lebanese Ministry of Tourism, the number of international arrivals to Lebanon dropped from around 2.17 million in 2010 to 1.21 million in 2013. Though, by the end of 2017 signs of recovery started showing with 1.86 million tourist arrivals and around 2 million in 2018. Despite this unstable situation, the tourism industry has witnessed positive changes since 2008. In parallel to the decline of conventional tourism in main Lebanese cities, alternative forms of tourism are prospering in rural areas, mainly providing nature and adventure-based tourism products. This new trend in the tourism market benefits from a unique natural and cultural landscape characterized by a combination of diverse ecosystems and distinguished biodiversity with many endemic species. (Abou Arrage et al., 2014; Abou Arrage, 2017)

Nonetheless, the ecosystems of Lebanon are threatened by a multitude of factors that are causing the loss of biodiversity, the fragmentation of habitats and different forms of pollution. In response to environmental degradation, the Ministry of Environment designated 14 Nature Reserves, in addition to 3 UNESCO Biosphere Reserves, covering around 2.2% of the Lebanese territory and constituting an important asset for ecotourism. Three out of the fourteen nature reserves and one biosphere reserves have ecotourism management plans and account the number of their visitors. The total number of visitors to these four reserves increased by 147% in the last eight years, from 72,000 in 2010 to 178,000 in 2018. The Shouf Biosphere Reserve remains the main attraction among these four reserves with the highest number of visitors (64%) due to its large size, advanced management, availability of services and activities, and accessibility (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Evolution of the number of visitors to Lebanon’s nature reserves

Source: Data collected from Nature Reserves managers

Although the concept of ecotourism was not spread among tourism professionals in Lebanon, the years 1995 to 2006 witnessed the rise of nature-based tourism with the establishment of the first seven nature reserves and the creation of six tour-operators offering nature-based tourism activities such as hiking, climbing, caving, paragliding, and rafting. Between 2007 and 2012, the existing nature reserves upgraded their strategies and prepared ecotourism management programs, seven additional nature reserves were established. The Lebanon Mountain Trail, a national hiking trail extending over 470 km, was created in 2008, and more than 30 local hiking trails were created through rural tourism and ecotourism development projects implemented with the support of international organizations. As a result, the number of nature-based tour operators increased to 25 by the end of 2012 (Abou Arrage, 2017).

Despite the political and security situation in the country between 2011 and 2018, a steady increase in rural tourism activities and accommodation services has been recorded and the number of nature-based tour operators increased to 42 in 2015 and reached 65 in 2018, which is considered a high number compared to the size of the Lebanese market (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Evolution of the number of nature-based tour operators in Lebanon

Source: Data collected from field work

4. Research methodology

The research objectives were to study the evolution and dynamics of ecotourism trends from nature-based tour operators’ perspective in Lebanon and to measure their specialization level in the existing supply market through the exploration of their profile and practices compared to the international ecotourism principles and guidelines. To achieve the research objectives a conceptual framework has been developed based on series of variables and indicators (Figure 4 and Table 2) where the dependent variables (DV) are: Ecotourism understanding and practices; and the independent variable (IV) are: nature-based tour operators’ awareness of the ecotourism concept, educational background of the tour operator owner, specialization level of the tour operator, market trends and dynamics followed by the tour operator, and the institutional framework of the tour operator. The compliance with ecotourism international principles is set as a DV reflected through the nature-based tour operators’ practices.

Figure 4: Research conceptual framework

The following hypotheses were developed to examine the relation between the dependent and independent variables:

(H1): ecotourism understanding and practices of nature-based tour operators are influenced by their awareness about the concept;

(H2): ecotourism understanding and practices of nature-based tour operators are influenced by their educational background and specialization level;

(H3): ecotourism understanding and practices of nature-based tour operators are influenced by the market trends and dynamics.

The field study was conducted in 2018 with 50 nature-based tour operators using a researcher administrated questionnaire including 27 open and closed ended questions guided by the literature review and designed to be exploited in descriptive and analytical statistics to examine the variability in different phenomena and the relationships between different variables in order to validate or reject the different hypotheses. The collected data was analyzed quantitatively in SPSS.

Table 2: Research variables and indicators

Source: Author's own research

5. Results and discussions

The educational background of the participants revealed that 96 % of the nature-based tour operators (NBTOs) in Lebanon do not have any degree related to tourism, and only 3 out of the 50 interviewed operators said that they have obtained professional certificates pertaining to sustainability and ecotourism. Concerning the institutional framework, more than the half of NBTOs (54%) are informal groups operating through social media platforms, 30% are registered as general commercial companies, 12% as NGOs, and only 4% are registered as travel agents.

The lack of proper legislation for nature-based and ecotourism activities is a major challenge in Lebanon. NBTOs working in a non-formal way do not have any official status or license. Therefore, their practices might be muddled due to the inexistence of any legal prosecution in case of environmental damages inside or outside nature reserves. Regarding the number of employees, 14 NBTOs have 2 to 5 permanent employees and 36 have 1 or 2 permanent employees; while 4 NBTOs use the services of 10 to 15 part timers, 19 have 5 to 10 part timers, and 27 have less than 5 part timers. The majority of the permanent and part timer employees are not officially registered and do not have rights based on the Lebanese labor law. These figures do not comply with the ecotourism principles that stress the importance of sustaining the wellbeing of local people and ensuring their source of income.

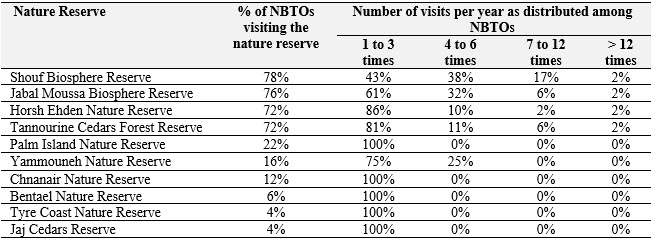

To measure their level of specialization, the NBTOs were asked about the number of their visits to nature reserves. The results showed that 78% of them include nature reserves in their tours. This figure reveals a good awareness regarding the ecotourism principle that stresses visiting protected areas and generating revenues to support their management and conservation. Table 3 shows that the Shouf Biosphere Reserve is the most visited reserved followed by Jabal Moussa, Horsh Ehden, and Tannourine reserves. This high percentage of visits to the top four nature reserves is related to the possibility of visiting them during different seasons with the existence of good infrastructure and management, as well as a wide range of activities. NBTOs do not give the same importance for all nature reserves in Lebanon due to multiple factors such as accessibility, activities, seasonality, management, services and infrastructure. Consequently, the economic contribution to conservation and local development is not equal between NBTOs neither between reserves in Lebanon.

Table 3: Percentage and frequency of visitation to nature reserves

Source: Author's own research

The survey showed that Hiking is by far the most spread activity with 88% of NBTOs offering it in their programs. Simultaneously, other activities such as snow activities, biking, camping, caving, mountaineering, kayaking and rafting are offered by 42% of NBTOs. On the other hand, activities such as bird watching, star gazing, participation in community events and cultural events, wildlife watching, culinary tourism and wine are offered by 8% of the NBTOs only.

The above findings show that most of the Lebanese NBTOs focus on few nature reserves and on limited activities related to ecotourism which affects their level of specialization. Furthermore, the results have shown that only 10% of the NBTOs offer training sessions to enhance their employees’ ability to manage visitors in sensitive natural and cultural settings. As for the percentage of income that derives from the tourism services and activities that they provide, 66% of respondents stated that tourism constitutes a minor source of income for them, 14% stated that tourism constitutes a complementary source of income, and 20% reported that tourism services constitute a major source of income.

When asked about their practices, all the respondents stated that they provide information to the visitors about the characteristics of the destinations prior and during the visit, and they prepare the visitors for cultural interaction with locals before departure. On the other hand, the provision of materials to inform the visitors about the importance of environmental conservation is done mainly on-site by 80% of the NBTOs. Concerning the financial contribution to conservation, 94% of the interviewed NBTOs considered that they are doing it through the payment of entrance fees to the visited nature reserves. Only 3 NBTOs showed a willingness to have additional financial contributions by paying a sort of green premium or donating up to 10% of their profits for nature conservation and community support. This shows very limited compliance with the ecotourism principle that stresses the importance of financial contribution to support both conservation efforts and community-based projects.

The results revealed that only 14% of the interviewed NBTOs respect the ideal group number for an ecotourism activity which is 12 to 20 persons per trip; while 18% allow between 21 and 40 persons, 38% have a group size ranging between 41 and 60 persons, and 30% between 61 and 100 persons per trip. Thus, the majority of NBTOs (86%) tend to constitute potential threats to the environment. This practice is contrary to what the ecotourism guidelines recommend regarding low visitor impact and being small scale.

Moreover, the results showed that 73% of the NBTOs organize one-day tours labeled under ecotourism banner, and 27% of them stated that the one-day tour constitutes around 70% of their total tours per year, while the remaining 30% are weekend tours. Nature-based tours extending for more than 3 days are rarely organized, especially for the domestic market. These results contradict the ecotourism principles related to local economic development, since one-day tour expenditures in the visited area are very low and do not benefit the accommodation services which are vital in ecotourism destinations.

The NBTOs who use accommodation services in their tours do not give a priority for Eco-lodges and guesthouses, 90% of them stated that they do not consider the eco-lodge as an accommodation option, and 64% do not use guesthouses. They rather use resorts, hotels, and camping sites, which do not match with the ecotourism concept and principles. Similar to accommodation, the results of the food and beverage services showed a weak comprehension of the ecotourism concept and principles related to this subject where 70% of the NBTOs do not use the services of local bakeries, snacks or restaurants, and ask the tourists to bring their own food, however they all stated that they encourage tourists to buy locally produced handicrafts and processed food. In terms of hiring local guides, 74% of the interviewed NBTOs stated that they do it.

As a reaction to the increasing demand for nature-based activities, 12% of the NBTOs are increasing the number of tours per week or per month, and 68% of them are increasing the number of tourists per tour. In the latter case, the small scale character of ecotourism and the low visitor impact on the destination is not respected. Only 20% of the NTBOs are not reacting to the market trends and do not have plans to increase the number of their tours or the number of tourists per tour. None of the interviewed NBTOs organizes disabled friendly tours; hence, this is an indicator of weak compliance with the inclusivity principle. On the other hand, 11 NBTOs organize elderly friendly trips, and 9 have tailor made tours for school students.

The last question of the survey asked the NBTOs to give a definition for ecotourism in their own words. Answers were analyzed based on the frequency of key words with reference to the IUCN definition of 1996 and TIES definition of 2015. The findings showed that:

Based on the above results, NBTOs have shown a weak understanding and awareness of the ecotourism concept. This weakness, which is reflected through their practices and interpretations, derives from the inexistence of any law that requires a degree or certificate in tourism or ecotourism for the workers in this domain. This was obviously represented through the high percentage (above 90%) of NBTOs who lack such degrees and certificates. As a result, this will weaken the specialization level of these nature tour organizers and will lead to uncontrolled nature activities that may harm the environment.

To analyze the relation that exists between the variables that influence the NBTOs practices, cross tabulation and Pearson Chi-square tests were done. The relationship that exists betweenthe maximum number of visitors allowed per tour (practice) and the ecotourism awareness revealed through the definitions given by NBTOs (concept awareness), showed that whenever the number of visitors per tour increased, the awareness about this ecotourism principle did not exist (Table 4).

Table 4: Cross tab between visitors’ number allowed per tour and low visitor impact

Source: Author's own research

Based on the Pearson chi- square test, the number of tourists allowed per tour as an ecotourism practice is changing with the level of awareness about the ecotourism. The obtained value is (0.021) which is less than the alpha value (0.05), thus the hypothesis (H1) is accepted: ecotourism understanding and practices of nature-based tour operators are influenced by their awareness about the concept. The relation between the educational background of the Lebanese NBTOs (profile) and the ecotourism awareness revealed through the definitions given by NBTOs (concept awareness) showed that NBTOs who do not hold any degree or certification in tourism or ecotourism have a very low level of awareness of the essential principles of the ecotourism.

The Pearson chi- square test for these two variables confirms the above result with a value of (0.025), thus the hypothesis (H2) is accepted: ecotourism understanding and practices of nature-based tour operators are influenced by their educational background. Furthermore, the relation between the maximum number of visitors allowed per tour (practice) and the response to the increase in demand for nature based tours (market trends and dynamics) showed that with the increasing number of visitors allowed per tour, the response was to market trends was the additional increase of number of visitors allowed per tour (Table 5). The Pearson chi-square test for these two variables was (0.000), thus the hypothesis (H3) is accepted: ecotourism understanding and practices of nature-based tour operators are influenced by the market trends and dynamics.

Table 5: Cross tab between visitors’ number per tour and NBTOs response to market trends

Source: Author's own research

The descriptive and analytical results presented in this paper confirm that the reasons behind the misuse and misinterpretations of the ecotourism term by the Lebanese NBTOs are, the lack of awareness about the concept, their low specialization level, their obedience to the market trends with very weak compliance with the internationally ecotourism principles and guidelines, and the inexistence of an institutional framework that to control their practices.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

The analysis of the relationship between nature-based tour operators’ profile in Lebanon and their ecotourism practices and level of awareness revealed that the term ecotourism is misused and misinterpreted. The study yielded considerable information about the evolution of ecotourism in Lebanon and revealed that two decades after the introduction of the concept to Lebanon, the level of specialization in ecotourism is still weak and the existing practices are not compliant with the international principles and guidelines. The majority of nature-based tour operators in Lebanon do not respect the principle of low visitor impact and did show a very low willingness to contribute financially to environmental conservation. In terms of activities, hiking is the dominant activity, while environmental education activities are ignored by the majority of operators. Consequently, ecotourism is not fulfilling its role in terms of sustainable development in Lebanon. However, the booming number of nature-based tour operators shows a constant evolution in the market trends.

Despite their low contribution to sustainable development in its three dimensions, the existing “ecotourism” products and activities bring benefits to the Lebanese rural areas, especially in terms of creating economic opportunities for local guides, rural accommodation facilities, and local producers. As for their contribution to conservations and socio-cultural preservation, they are limited to a very small number of stakeholders, namely some leading nature reserves and few pioneer tour operators.

In order to have a more sustainable form of ecotourism in Lebanon, it is essential to improve the institutional framework, especially on the supply level, with the creation of specific rules and regulations for operators who would like to offer ecotourism services and activities. On the other hand, introducing the ecotourism concept to the Lebanese society through the educational system might be a good strategy to enhance its role in sustainable development. Further researches may enclose the study of the legal perspectives that might impose regulations on the practitioners.

Received: 15 March 2019; Sent for revision: 10 May 2019; Accepted: 17 May 2019