| Review Article | UDC: 338.48-6:615.83]:94(497.1)"1926/1940" |

Jelena Radović Stojanović1 , Dragana Gnjatović2

1University of Criminal Investigation and Police Studies, Belgrade, Serbia

2University Business Academy Novi Sad, Faculty of Social Sciences, Belgrade, Serbia

Abstract: The paper presents statistical data on spa tourism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the period from 1926 to 1940. The sources of data for the research were the Statistical Yearbooks of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The paper aims to show how spa tourism statistics and tourism statistics in general developed in the years between the two world wars. Furthermore, the paper aims to provide a picture of the level of development of spas and spa tourism in the Kingdom through the presented data. Illustrative data on hotel capacities for some of the most famous spas in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia are presented. A combination of historical and statistical methods was used to analyze statistical data on spa tourism and the financial effects of tourism. The existing data made it possible to calculate the share of revenues from spa tourism in both the total revenues from tourism and the national income of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Keywords: spa tourism, spas, mineral waters, tourism statistics, Kingdom of Yugoslavia

JEL classification: Z31, Z32

Statistika banjskog turizma u Kraljevini Jugoslaviji

Sažetak: U radu su prikazani statistički podaci o banjskom turizmu u Kraljevini Jugoslaviji za period 1926-1940. godina. Izvori podataka za rad bili su statistički godišnjaci Kraljevine Jugoslavije. Cilj rada je da prikaže kako se razvijala statistika banjskog turizma i statistika turizma uopšte u godinama između dva svetska rata. Još jedan cilj je da se kroz prikazane podatke pruži slika o nivou razvijenosti banja i banjskog turizma u Kraljevini. Prikazani su ilustrativni podaci o hotelskim kapacitetima za neke od najpoznatijih banja u Kraljevini Jugoslaviji. Kombinacijom istorijskog i statističkog metoda analizirani su statistički podaci o banjskom turizmu i finansijski efekti turizma. Postojeći podaci omogućili su izračunavanje udela prinosa od banjskog turizma u ukupnim prinosima turizma i u nacionalnom dohotku Kraljevine Jugoslavije.

Ključne reči: banjski turizam, banje, lekovite vode, statistika turizma, Kraljevina Jugoslavija

JEL klasifikacija: Z31, Z32

1. Introduction

The beginnings of the rich and colorful history of spas and spa tourism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia date back to the time of the ancient Romans, who were the first in this area to use mineral waters for healing purposes. In more recent past, in the 19th century, especially in Serbia, these beginnings were associated with the organized and systematic testing of mineral waters. In 1835, at the invitation of Prince Miloš Obrenović, the German geologist Baron Sigmund August von Herder performed the first tests of chemical composition of mineral waters from 16 places in Serbia (Ljušić, 2008, p. 72). Several more decades passed from then until the appearance of organized spa tourism. At the end of the 19th century, spa baths were arranged and the first hotels were opened. By the beginning of the First World War, all today known forms of tourism developed - going to the sea, hiking, excursion tourism and going to spas, and the most famous tourist places in the future Kingdom of Yugoslavia were Dubrovnik, Opatija and Vrnjačka Banja.

In Serbia, the establishment of the Society of Healing Mineral Hot Water in Vrnjci in 1868, the construction of roads and railways were important for the beginning of organized spa tourism (Lazić, 2015). The very next year, in 1869, the first data on tourism were recorded in Vrnjačka Banja. Thus, it was noted that Vrnjačka Banja was visited by 583 visitors who stayed there for a total of 16,140 days. Official statistical data on visits to this spa resort have been recorded since 1898. Until then, the records had been collected by district and county doctors who administered the resort (Ruđinčanin & Topalović, 2008). These were the beginnings of organized data collection on spas, until the State took over this activity. The first Law on Spas, Mineral and Hot Waters was passed in Serbia in 1914 (Krejić et al., 2017). With this law, all spas were nationalized: “…all mineral and hot waters are state property...” (Law on Spas, Mineral and Hot Waters, 1914). Until then, some of them were also privately owned (Marković, 1980). The first Law on Spas stipulated that the State would supervise and improve the work of spas. However, this had to wait until the end of the First World War.

Organized tourist activity in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia continued to develop after the end of the First World War. A congress was held in Zagreb on December 30, 1920, at which the Association of Baths, Spas, Climate Places, Mineral Springs and Sanatoriums in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was founded and a proposal was given for the establishment of the Department for Foreign Visitors at the Ministry of Trade and Industry (Lazić, 2015). At this Congress, a proposal was also made for the establishment of a special company that would have travel offices in all important places in the Kingdom. Thus, in 1923, the first travel agency in today’s sense of the word was founded under the name “Putnik”, as a joint stock company for passenger and tourist traffic in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Krejić & Milićević, 2018). Among the branches of this company, the first one was opened in Vrnjačka Banja in 1927 (Krajčević, 1998). The establishment of this travel agency gave an additional impetus to the growth of tourist visits.

During the 1920s, organized visits of not only domestic but also foreign tourists began. The first official, although incomplete statistical data show that in 1924, Yugoslav resorts, spas, climatic places and cities were visited by 120,000 foreign tourists, of which an income of between 300-400 million dinars was recorded (Yearbook of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes 1926., p. 434). In those first years after the end of the First World War, the number of visitors to certain tourist destinations and spas as well as the most important data on thermal waters in the Kingdom were recorded. Shortly afterwards, the organized collection of data on spa tourism and tourism in general began. Starting from 1929, those data were regularly published in the Statistical Yearbook. The categorization of spas and their division into three categories was undertaken in 1924. Thus, for example, Vrnjačka Banja, Rogaška Slatina and Banja Lipik were ranked in the first category of spas (Ruđinčanin & Topalović, 2008).

The number of visitors in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia grew from year to year. In 1932 and 1933, during the Great Depression, there was a stagnation. Then, after the end of the crisis, a rapid recovery of tourism occurred. The largest number of tourists was recorded in 1935, when 767,000 domestic tourists were registered in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia who stayed in coastal places, spas and at the mountains (Krejić & Milićević, 2018). That year, 45 spas were listed in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (Niketić, 1935). In the following years, the total number of visitors was close to 700,000 per year where almost one fourth visited the spas. In 1938, for example, 160,295 persons visited spas (Statistical Yearbook 1938-1939, pp. 324–326) and 1939, their number amounted to 139,849 (Statistical Yearbook 1940, pp. 306–308). In more detail, data on tourist visits, as well as other statistical data on spas for the period from 1926 to 1940, are presented here in the paper.

2. Statistics on spa tourism

The first official statistical data on spas and spa tourism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia were published in 1926, in the Statistical Yearbook of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. This was the first Statistical Yearbook published after the end of the First World War. Spa tourism has been extensively explained within the chapter Public Health in Yugoslavia, in the section entitled Mineral waters, muds, sea baths and climate places. Although in this Yearbook there were no detailed data on spas and their hotel capacities, as would be the case with the Yearbooks that followed, in the aforementioned section there is a large amount of data that provide insight into the level of development of spa tourism. Thus, it has been stated that the Standing Spa Committee at the Ministry of Public Health counted 300 mineral springs on the territory of the Kingdom, and that a number of these springs had been very well arranged and attracted a large visitor audience. It has been also noted that the most visited spa was Vrnjačka Banja in Serbia with 23,000 visitors, then Topusko in Croatia with over 7,000 visitors. Those two spas were followed by Rogaška Slatina and Rimske Toplice in Slovenia, Banja Ilidža near Sarajevo in Bosnia and Banja Koviljača in Serbia, with more than 5,000 visitors each. According to this source, among rather visited spas in Serbia were also Vranjska banja with 3,000 visitors and Ribarska banja, Sokobanja and Jošanička banja with 2,000 visitors each, as well as Krapinske Toplice in Croatia with 2,000 visitors. Then, the characteristics of water, chemical composition and temperature of well-known waters were described, as well as the treatments in which healing water was used (Yearbook of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes 1926., pp. 375–384).

The official data on spas and spa tourism began to be published regularly starting with the Statistical Yearbook for 1929, which was the first Yearbook published after the one from 1926. In the Yearbook for 1929, within the chapter on Health Conditions there is a section entitled Healing waters, climate and tourist places which was dedicated to spa tourism. In this section, there is a table under the same name, in which it was noted that there were 288 healing waters on the territory of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, of which 46 spas were of the first and second category (Figure 1). Since from 1929, the territory of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was divided administratively in nine regions (banovina), with capital city each: Dravska (Ljubljana), Savska (Zagreb) Vrbaska (Banja Luka), Primorska (Split), Drinska (Sarajevo), Zetska (Cetinje), Dunavska (Novi Sad), Moravska (Niš) and Vardarska (Skoplje), statistical division of healing waters was made according to their regional location. Thus, the largest number of healing waters was located on the territory of Drinska Banovina (66), then on the territory of Moravska Banovina (62), followed by Vardarska Banovina (37) and Dunavska Banovina (29) (Statistical Yearbook 1929, p. 413).

Figure 1: Healing waters, climate and tourist places in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929

Source: Statistical Yearbook 1929

In a separate table called Spas, significant spas located in particular regions are listed, the rank of the spa (I or II category) is recorded, the chemical composition of water for each spa is described as well as diseases treated in each spa (Statistical Yearbook 1929, pp. 414–419). Finally, a table entitled Other mineral and healing waters by regions is given, which lists all healing and mineral waters in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (Statistical Yearbook 1929, p. 420). Data on spas could be also found in the chapter of this Yearbook called Hotel Industry. In this chapter, in the table entitled Hotel industry in 1929 by banovinas and capitals of the banovinas, the hotel capacities of the most important tourist places, number of hotels, their equipment, their distance from a railway or steamship station and many other data were presented. Among these data, information on individual spas was shown. From year to year, the number of tourist and spa places for which data on hotel capacities were published was increasing.

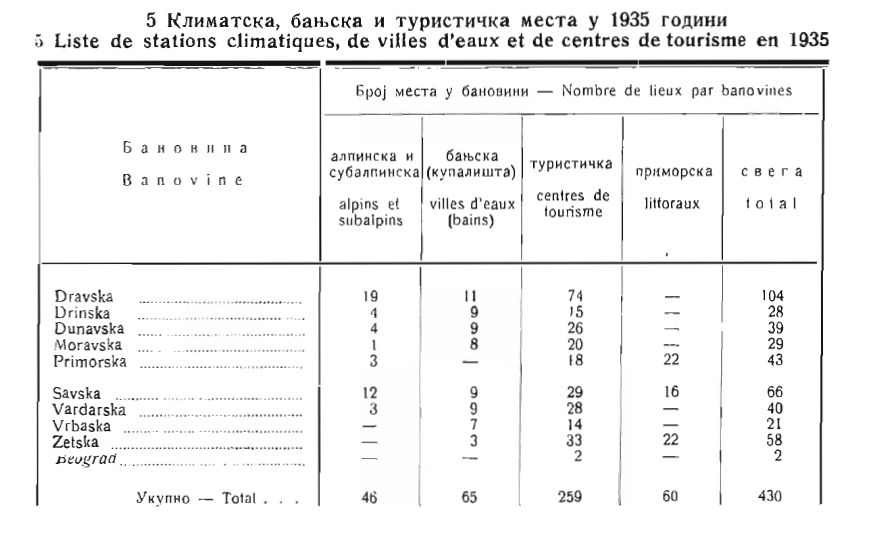

The data on spas and healing waters were presented in this way until the Statistical Yearbook for 1934 and 1935 (one joint Yearbook for these two years was published), in which there was a change in the way of presenting them. In this Yearbook, data on spas were presented within the chapter Tourism, instead of, as before, in the chapter dedicated to health conditions. There, within the table called Visitors - Tourists only data on the number and citizenship of visitors for all tourist places in the Kingdom were presented, among which were the data for spas. Healing water data were not published in this Yearbook and were not published at all afterwards. In the Statistical Yearbook for 1934 and 1935, the data on spas could only be found in the table called Climate, spa and tourist places in 1935, in which the number of tourist places in the Kingdom by their types was recorded (Figure 2). The table states that there were a total of 65 spas in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1935 (Statistical Yearbook 1934–1935, p. 245).

Figure 2: Climate, spa and tourist places in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1935

Source: Statistical Yearbook 1934-1935

In the Yearbook for 1936, data on tourism and spas were presented in the same way as in the Yearbook for 1934 and 1935. The tables called Overview of tourism by years, Climate, spas and tourist places, Revenue from tourism and Visitors-Tourists have been presented. New in this Yearbook are two tables dedicated to mountaineering: Members of the union of mountaineering associations and Centers of the mountaineering associations, while there were no more detailed data on spa tourism (Statistical Yearbook 1936, pp. 287–295).

In the Yearbook for 1937, the way of statistical coverage of tourism changed again. The table Climate, spa and tourist places, in which the number and type of tourist places were previously recorded, in this Yearbook has not been presented. What has been presented in the table entitled Visitors - Tourists in 1937 was an overview of visits to tourist places by banovinas in the Kingdom (number of visitors and their citizenship) (Statistical Yearbook 1937, pp. 238–241). As in previous Yearbooks, data on tourist visits for all known spas have been presented among other data in this table. In the Yearbook for 1938. and 1939 (joint edition for both years) and the Yearbook for 1940, a table has been published entitled Tourist traffic by banovinas, in which all tourist places have been divided into tourist places in a narrower sense, tourist places of climatic-mountain character, tourist places of climatic-coastal character and tourist places of spa character and for all these tourist places the number and citizenship of visitors was shown (Figure 3). Then, in the table entitled Visitors - Tourists by places, the tourist visits to all important tourist places and the citizenship of the visitors have been shown. There were no other data on spa places, such as data on mineral waters or hotel capacities of spa places in these Yearbooks.

Figure 3: Part of the table entitled Tourist traffic by banovinas in 1938, Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Source: Statistical Yearbook 1938-1939

Data on spas, together with the data on climate and tourist places, were collected by the Ministry of Social Policy and Public Health. For data on tourism in general, also known as hotel industry, the Ministry of Trade and Industry was responsible. The source for data on the writings entitled Lekovite vode, klimatska i turistička mesta (Healing waters, climate and tourist places) in the Yearbook for 1929 was a publication of the Ministry of Social Policy and Public Health entitled Lekovite vode i klimatska mesta (1922) (Healing Waters and Climate Places (1922). Furthermore, the unpublished official materials of the Ministry of Social Policy and Public Health as well as the documents of the Royal Regional Administrations served as a source of data for this analysis (Statistical Yearbook 1929, p. 399). These two unpublished sources were also cited as sources of data on spa tourism in the following Statistical Yearbooks, concluding with the Yearbook for 1933.

Starting from the Yearbook for 1934 and 1935, where the data on spas were presented within the chapter Tourism, the official reports of the Ministry of Trade and Industry, the Department of Tourism and the publication of the Department of Tourism entitled Tourism Policy, Volume I for 1936 have been cited (Statistical Yearbook 1934-1935, p. 235). These same sources were cited as sources of data on tourism in the Yearbook for 1936 (Statistical Yearbook 1936, p. 287). In the Statistical Yearbook for 1937, in addition to those already listed, the source Zvanični izveštaji pograničnih komesarijata koji vode evidenciju ulaska i izlaska putnika (Official Reports of Border Commissariats Keeping Records of Passengers' Entry and Exit) has also been cited (Statistical Yearbook 1937, p. 235). These sources remained the same in the Statistical Yearbook for 1938 and 1939 and in the Statistical Yearbook for 1940, which was published in 1941.

3. Hotel capacities of well-known spa resorts

Data on hotel capacities of tourist places appeared first in the Statistical Yearbook for 1929 and were published concluding with the Statistical Yearbook for 1933. The data were published within the chapter entitled Hotel industry for 1929 onwards and then from the Statistical Yearbook for 1933 this chapter was renamed Tourism. A large table on several pages entitled Hotel industry by banovinas and the capital of the banovinas showed in detail the data on hotel capacities in the largest tourist places. In the table, the number of hotels in tourist places can be seen as well as their distance from the railway or steamship station, and the number of hotels having a telephone, garage and elevator, reading room, theater, cinema, tennis court. We find out the number of hotels that had a salon, dance hall, variety and bar, and what the rooms in the hotels were like; the number of hotels that had a shared bathroom or en-suite one; the number of hotels with a warm or cold water and whether the rooms were mostly single, double or multi-bed. The special table called Hotel visitors and their citizenship by banovinas records the number of visitors by places, their citizenship and time of stay in tourist places (passers-by, up to 15 days and longer than 15 days).

Thus, we learn that Vrnjačka Banja, the largest and most visited spa in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, located in Moravska Banovina, central Serbia, was visited in 1929 by 24,564 persons mostly from the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (24,415). There were some foreign tourists from Greece (106) and a few from Austria, Germany, France and the surrounding countries. In 1929, Vrnjačka Banja had 50 hotels, with a reading room (15 hotels), verandas and a terrace (6 hotels), a salon and an orchestra (3 hotels) and even a tennis court (1 hotel). All hotels had a restaurant, electric lighting and cold water in the rooms and 13 had a bathroom for the whole hotel. The rooms were mostly single (400 rooms) and double (250 rooms) and in total there were 900 beds in hotels. In 1929, 466,716 overnight stays were realized (Statistical Yearbook 1929, pp. 318–321). It has also been noted that the healing water in Vrnjačka Banja was alkaline acid homoeothermic and cured diseases of kidneys, liver and digestive organs.

At the western part of the Kingdom, Banja Bled in Dravska Banovina, in Slovenia, had 16 hotels. This Spa was known for its alkaline water springs that cured respiratory diseases and nerve diseases. Out of 16 hotels, 14 had a telephone, 10 a garage and six their own car. Seven hotels had verandas and terraces and three had their own reading room. All hotels had electric lighting and 13 had their own restaurant. There were 10 hotels with hot water in the rooms and the same number of hotels had a bathroom for the whole hotel. Banja Bled had 500 one-bed rooms, 450 twin rooms and no multi-bed rooms. There were 1,400 beds in 950 rooms. In 1929, 16,996 visitors spent 237,944 nights there. Most guests in hotels were from the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (6,460), followed by foreign visitors, from Germany (4,520), Austria (2,519) and Czechoslovakia (1,974), and there were also guests from Hungary (771), Italy (201), England (81) and France (41) (Statistical Yearbook 1929, pp. 318–321).

Banja Koviljača, a small but well-known spa in Drinska Banovina, in western Serbia, had only four hotels. All four hotels had their own thermal bathroom, two had verandas and terraces and two even a tennis court, orchestra lounge and dance floor. In 1929, Banja Koviljača had 6,321 visitors who spent 94,815 nights there. All visitors were from the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and all stayed there for more than 15 days. The spa had 134 single rooms and 67 double rooms. On the overall, there were 268 beds in 201 rooms (Statistical Yearbook 1929, pp. 318–321).

Bukovička Banja in Dunavska Banovina in the heart of Serbia has been known for its park and alkaline sulfur and very iron waters that treat skin and women's diseases, diseases of the digestive organs and stomach diseases. In 1929, it had 10 hotels and all hotels had their own restaurants. The Spa had 46 single rooms and 26 double rooms, which makes 72 rooms with 98 beds. That year, 3,000 visitors spent 9,000 nights in the hotels of Bukovička Banja. All visitors were from the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (Statistical Yearbook 1929,pp. 318–321).

In Primorska Banovina, in Croatia, Banja Split near the city of Split was well-known. Salty, sulfur-saline hypothermic water with a larger amount of bromide treated rheumatism and respiratory diseases. In the Statistical Yearbook for 1929, there was no information about the Spa itself, but it could be found that the city of Split had 10 hotels with a restaurant and electric lighting, 8 of which had a bathroom for the entire hotel. There were 157 single rooms, 168 double rooms and nine multi-bed rooms. In 334 rooms, there were 528 beds with 34,210 visitors staying in them. Most visitors (20,514) were from the territory of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and there were a lot of foreign tourists, mostly from Germany (4,844), Austria (3,675) and Czechoslovakia (2,277) (Statistical Yearbook 1929,pp. 318–321).

The methodology of presenting data on hotel capacities and tourist visits in spa places in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was not changed in the period from 1929 to 1932. However, over time, the number of spas for which data were collected increased. Thus, in the Statistical Yearbook for 1933 we see data on hotels and tourist visits for other spas as well (Kuršumlijska Banja, Mataruška Banja, Niška Banja, Ribarska Banja, Soko Banja in Moravska Banovina; Vranjska Banja, Debarska Banja, Katlanovska Banja, Kosovratska Banja in Vardarska Banovina, Rogaška Slatina in Dravska Banovina, etc.). In the section devoted to health conditions, the mineral composition of the waters of these spas was given, as well as the diseases in the treatment of which they were used (Statistical Yearbook 1933, pp. 245–254). In the Statistical Yearbook for 1934 and 1935, all these data, as stated in the previous part of the paper, were no longer available. The mentioned Yearbook, as well as those that followed, focused on the recording of the total tourist visit. The total number of visitors, the number of overnight stays, the citizenship of the visitors and the financial effect of the tourist activity were recorded and published (Statistical Yearbook 1934-1935, pp. 235–246).

4. Financial effects from spa tourism

Data on tourism revenues were first published in the Statistical Yearbook 1934-1935. In the section Tourism, page 244, a table is given entitled “Financial effects from tourism”. It presents the financial revenues from tourism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the period from 1930 to 1935. It also included the income from tourism for climate places (coastal and alpine and subalpine), spas, tourist places and finally, financial income from tourism – in total. The table with data on financial income from tourism was published once again, in the Statistical Yearbook for 1936, page 288 (Figure 4). After that, data on financial effects from tourism did not appear in the Statistical Yearbooks published until the Second World War.

Figure 4: Financial effects from tourism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia 1930-1936

Source: Statistical Yearbook 1936

Based on the data from Figure 1, the percentage share of the revenues from different forms of tourism in the total revenue generated from tourism was calculated and shown in Table 1. It can be seen that the share of spa revenues in total revenues generated from tourism was highest in 1931 when it amounted to 22.6%. Then, a decrease was recorded until 1934, when it amounted to 15.8%. The reason for this trend was relatively larger decline in revenues from spa tourism than the decline in total tourism revenues during the Great Depression that lasted from 1929 to 1933.

As shown in Table 1, after 1934, a positive trend in the share of spa revenues in total revenues from tourism was recorded. In 1936, the share of spa revenues in total revenues from tourism reached 20.2% and was almost at the 1930’s level. This happened because spa tourism recovered from Great Depression more quickly than other forms of tourism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Table 1: The share of revenues from different branches of tourism in the total revenue generated from tourism, Kingdom of Yugoslavia, 1930-1936, in %

|

Coastal climate places |

Alpine and subalpine |

Spas |

Tourist places |

Total |

1930 |

40.4 |

10.4 |

20.6 |

28.6 |

100.0 |

1931 |

41.0 |

10.0 |

22.6 |

26.4 |

100.0 |

1932 |

41.1 |

12.8 |

19.1 |

26.9 |

100.0 |

1933 |

36.1 |

11.7 |

16.9 |

35.1 |

100.0 |

1934 |

32.6 |

8.2 |

15.8 |

43.5 |

100.0 |

1935 |

31.5 |

8.0 |

18.4 |

42.0 |

100.0 |

1936 |

35.3 |

11.2 |

20.2 |

33.4 |

100.0 |

Source: Author’s research

Using the data presented in Figure 4, the share of revenues generated from tourism in general and spa tourism in particular in the national income of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia have been calculated. Regarding the data on the national income of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, since the General Government Statistics of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia did not publish data on national income, they were taken from Stevan Stajić’s study National income of Yugoslavia 1923-1939 in constant and current prices (Stajić, 1959). According to Gnjatović (2016), “This study has been accepted internationally as a relevant source of statistical data on the national accounts of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia” (p. 24).

Table 2: Share of the revenues from tourism and spa tourism in the national income of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, 1930-1936, in %

Year |

National income in current prices |

Revenues from tourism |

Revenue from spa tourism |

Share of the revenues from tourism |

Share of revenues from spa tourism |

1930 |

50,418,200 |

605,530 |

124,771 |

1.2 |

0.2 |

1931 |

45,099,700 |

530,544 |

12,005 |

1.2 |

0.0 |

1932 |

36,480,900 |

492,905 |

94,234 |

1.4 |

0.3 |

1933 |

36,117,000 |

701,905 |

118,773 |

1.9 |

0.3 |

1934 |

34,065,700 |

811,107 |

128,159 |

2.4 |

0.4 |

1935 |

34,602,300 |

827,154 |

152,434 |

2.4 |

0.4 |

1936 |

40,744,000 |

845,562 |

170,467 |

2.1 |

0.4 |

Source: Data on the national income of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia: Stajić (1959); Data on revenues from spa tourism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia: Statistical Yearbook 1936 Author’s research

Table 2 shows that the share of revenue from tourism in the national income of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was 1.2% in 1930. Over time, this share increased, so that in the period 1930-1936, the share of tourism in national income doubled. In this period, the share of revenues from spa tourism in the national income also increased. As the share of revenues from spa tourism in total revenues from tourism was relatively stable, amounting to 20% (Table 1), its contribution to national income also doubled.

5. Conclusion

The General Government Statistics of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia regularly collected data on spa tourism and published them in Statistical Yearbooks from 1929 to 1940. Initially, data on thermal waters, hotel capacities of spa places and classifications of tourist and spa places were published. Over time, the method of statistical coverage of spa tourism changed, with more importance attached to tourist visits and financial effects than the spa and hotel facilities. Tourism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was expanding between the two world wars, thus spa tourism also flourished. The interest was to show the financial results of that expansion, and the growth of the number of visitors and the changes in their structure according to their country of origin.

Available data on revenues from spa tourism made it possible to analyze the financial effects of this industry and calculate the share of spa tourism revenues in both total tourism revenues and national income. This was a challenging task given that data on national income were not available in the Statistical Yearbooks of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and that tourism was not a separate industry at the time and was statistically covered by the Ministry of Trade and Industry. The fact that today, at least in the Republic of Serbia, we do not have official statistical data on the realized revenues from spa tourism shows how advanced the tourism statistics was at that time. The achieved share of income from tourism in the national income of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia of 2.4% and the share of spa tourism amounting to 0.3%-0.4% is not negligible having in mind the level of development and the difficult economic situation in the Kingdom between the two wars. Today, this share of tourism in the gross domestic product, for example, in the Republic of Serbia is 1.1% (Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia, 2020).

The wealth of statistical information provides numerous opportunities for further research and analysis of the development of spa tourism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Presented data give an insight into the level of development of the General Government Statistics of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia between the two world wars and an insight into the achieved level of the statistical coverage of tourism. The data evoke the level of development of spa tourism and spa life at that time, an entire era that remains golden in the development of tourism. Based on the data, it is possible to further investigate how tourism developed and how tourist traffic grew, and in the period between the two wars to look for and find the roots of the growing popularity of spa tourism in the future Yugoslavia. So far, only a small number of researches have dealt with this period in the development of tourism and the place and importance that tourism had in the economy of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Presenting statistics on tourism, through research on how to collect the sources of statistics, this paper has allowed this gap to slowly begin to be filled.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Received: 11 October 2021; Sent for revision: 26 October 2021; Accepted: 1 December 2021